Seeking what not to seek: How to align achievement and happiness

- Jeff Hulett

- Jun 18, 2024

- 29 min read

Updated: Sep 10, 2025

Are you chasing success but still feel unfulfilled? The quest for achievement often collides with the elusive pursuit of happiness, leaving many wondering if the two can truly coexist. As a naturally competitive person, I have felt this tension firsthand. Whether competing in youth sports, college rugby, advancing in a job, coaching my children's sports teams, marketing loan products, selling consulting services, or striving to be the best entrepreneur and professor, competition has always been a part of my life. I know I’m not alone—competition is deeply ingrained in many of us.

In this article, Seeking What Not to Seek, I am not trying to convince you to stop competing. Quite the opposite—by channeling our competitive instincts, we can get more out of competition and life. We will unravel the paradox of seeking—why work-life balance feels so different for each of us and why what you pursue might be leading you astray. By understanding what not to seek, you can unlock the key to lasting happiness by winning the 'right' competition.

Dive in to discover a framework that helps you navigate this delicate trade-off, channel your competitive drive effectively, and adapt as your priorities evolve. The article concludes with resources to aid in your journey.

About the author: Jeff Hulett leads Personal Finance Reimagined, a decision-making and financial education platform. He teaches personal finance at James Madison University and provides personal finance seminars. Check out his book -- Making Choices, Making Money: Your Guide to Making Confident Financial Decisions.

Jeff is a career banker, data scientist, behavioral economist, and choice architect. Jeff has held banking and consulting leadership roles at Wells Fargo, Citibank, KPMG, and IBM.

Table of Contents

Introduction and work-life balance

Our evolutionary drive to seek

How much income should we seek to be happy?

Seeking by knowing what NOT to seek

Seeking and not seeking the road to happiness

Concluding with the seeking road

Notes and appendix

In today’s modern world, work has become the primary channel through which we fulfill our innate drive to seek. Whether we're striving for income, impact, recognition, or autonomy, work reflects many of the competing desires embedded in our biology and shaped by culture. This makes it an ideal lens for understanding our broader seeking nature. By examining how work intersects with autonomy, time control, and well-being, we can uncover both the rewards and risks of our seeking instincts. With this backdrop, we’ll explore why we seek, how much income supports happiness, what not to seek, and ultimately how to direct our seeking toward a more fulfilling life.

To begin, we define work-life balance as a personal concept, evolving over time and holding different meanings for each individual. Here are a few essential characteristics that shape our experience of work-life balance:

Independence: Independence, or autonomy, plays a critical role in balance. The ability to make decisions and pursue desires varies by work situation, either enhancing or diminishing autonomy. When work limits choices, it feels more demanding. Higher autonomy supports work-life balance.

Time Control: Time control doesn’t mean avoiding work but instead doing it on our own terms. This perception of time management depends on the work environment. Work feels heavier when it restricts time allocation. Greater control over time makes balance achievable.

Positive Attitude: A positive attitude can sometimes bridge negative feelings about work, helping us through challenges. In the longer term, though, building independence and controlling time fundamentally enhance our relationship with work. A positive attitude serves as a temporary support to help us navigate a difficult period. It should not be mistaken for the challenging decision-making required for meaningful change in our lives.

What is Happiness? Happiness is intensely personal and defined differently for each individual. Adam Smith, as a moral philosopher, described happiness in terms of two fundamental, social-based desires: to be loved and to be lovely—or, in modern terms, to be respected and to act in ways worthy of respect. [i-a1] This perspective, grounded in empathy and authenticity, has stood the test of time. Smith believed that happiness arises from balancing self-interest, which can encompass both selfish desires and selfless care for others, all guided by moral principles like the golden rule. His philosophy offers a timeless reminder that what we seek must align with our values and relationships.

Increasing autonomy and time control shifts the nature of work. Put simply, more freedom to manage work improves our relationship with it. This aligns with self-determination theory, which emphasizes that autonomy is a core psychological need essential for motivation, personal growth, and well-being. [i-a2] The pandemic highlighted this, as remote work increased both employee happiness and productivity—a clear win-win [i-a3]. With more freedom, work feels less demanding. For example:

Small Business Owner: They choose clients and allocate time to serve them. Though they still work, their independence often surpasses that of a traditional employee, making work feel less restrictive.

Parent of Young Children: Parenting has time demands, but parents have choices in raising their children, influencing the time dedicated to parenting. Work feels manageable when time control exists.

Both small business owners and parents possess the independence to make situational decisions. Freedom is not a perfect solution—small business owners may face intense deadlines, for instance. Yet, these are their decisions, not directed by someone else. For both, increased responsibility brings greater control over time and increased autonomy.

A Personal Perspective on How Work Feels in Banking:

As a career banker with experience on both sides of the 2008-09 financial crisis, banking once felt more enjoyable, with greater freedom to serve customers' best interests. My teams were committed to the highest ethical standards, but a few bad actors made harmful decisions, contributing to the crisis. Instead of enhancing supervision, legislators imposed rigid, prescriptive laws, essentially declaring: “You’ve lost our confidence, so we’ll dictate how to do your job.”

The challenge? Legislators often lack the expertise to regulate a dynamic banking sector, leading to outdated and inflexible prescriptions. Regulatory oversight has surged almost 20-fold in volume, limiting banks’ ability to adapt to evolving customer needs. [i-a4] Today’s banking environment requires banks to "check the box" rather than innovate, swinging from independence to rigid bureaucracy. Unsurprisingly, many skilled professionals have left traditional banking for FinTech and other non-bank sectors, seeking greater flexibility and autonomy.

Work-life balance is more achievable with freedoms encouraging our happiness. However, a necessary foundation for our happiness is having enough income above some minimum threshold. Until our basic needs are satisfied, freedoms such as independence and time control hold little significance.

Therefore, achieving work-life balance involves a continuous pursuit of various features, including work, income, family, autonomy, time management, and personal growth—all of which ultimately impact our happiness. In other words, achieving work-life balance requires ongoing seeking. Achieving work-life balance relates to how we seek and what we seek. With only 24 hours in a day or 168 hours in a week, our time is a fixed resource, requiring careful trade-offs between these essential aspects of life. Each person’s capacity—like their life “bag”—may differ; some bags are bigger, while others are smaller. Yet for most, it feels like their bag is overflowing, as though they are trying to shove 10 pounds into a 5-pound bag. Recognizing these limits helps us prioritize and align our efforts with what truly matters most.

Understanding our seeking starts with answering two fundamental questions:

Why do we seek? and

How much money should we seek to achieve happiness?

In Section 2, we examine why we seek—drawing from evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and social psychology to explain our deeply rooted drive.

Section 3 explores how much income is truly needed for happiness—debunking myths about wealth and revealing when seeking more begins to deliver diminishing returns.

Section 4 introduces a framework for what not to seek—identifying five common traps that often undermine well-being.

Section 5 then shifts toward how to direct our seeking constructively—aligning our efforts with long-term purpose, moral principles, and personal meaning.

This journey is about transforming seeking from an unconscious instinct into an intentional strategy for happiness.

2. Our evolutionary drive to seek

Humans are fundamentally hardwired to seek. [i-a5] This drive comes from our genome and evolutionary biology, where survival often depended on actively pursuing scarce resources. For our ancestors, seeking was critical for overcoming hunger and protecting the family. Every person’s existence today is the result of this relentless seeking over generations. If even one ancestor had failed to overcome scarcity and died before having children, your entire lineage—including you—would not exist. This relentless drive to seek is not just instinct; it is evolution’s uncompromising mandate for survival.

In today’s information-abundant world, this ancient drive persists, yet manifests in new and complex ways. [i-a6] Instead of seeking physical resources, we often pursue wealth, status, and validation in a society where we’re constantly exposed to others’ curated lives and achievements. Social media, for instance, intensifies our seeking drive, fueling “Fear of Missing Out” (FOMO) and the desire to “keep up with the Joneses.” The constant comparison triggered by these platforms pushes us to match or surpass what we see, whether it’s someone’s lifestyle, success, or material possessions.

However, our drive to seek extends beyond material resources. Evolution shaped humans to form social bonds within tribes, where mutual support increased the chances of survival. [i-a7] Adam Smith’s moral philosophy reflects this social nature, emphasizing the desire to be both “loved” and “lovely”—to be respected and to act in ways worthy of respect. This instinct to connect with others through meaningful relationships reinforces the idea that seeking must align with empathy and authenticity to foster lasting happiness.

This desire to be "loved" and "lovely" often extends into how we present ourselves to others, driving a focus on appearances and perceived status. Appearances can still deceive. In today’s consumer finance world, many use debt to project wealth, creating an illusion of success while their freedom remains constrained by financial obligations. True wealth and fulfillment are often invisible, yet our genome struggles to distinguish between real and perceived achievements, making the drive to seek both a blessing and a challenge in modern society.

Our culture amplifies this hardwired-seeking nature, particularly in countries like the U.S., where achievement is celebrated. The Constitution, Bill of Rights, and other social institutions reinforce a competitive ethos, supporting the “pursuit of happiness” as an individual endeavor that ultimately benefits society. [i-b] This achievement-focused environment, however, can blur the lines between healthy and unhealthy seeking. Without clear guidance, people are left to interpret what “happiness” and “success” mean for themselves. This article’s core thesis is that while seeking can be beneficial, knowing what not to seek is essential for well-being in an age of information overload.

Time-tested religions also offer insights into managing our seeking nature. [i-c] Across Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism, Hinduism, Confucianism, Taoism, and others, teachings address the risks of unchecked desire. In Christianity, for example, James 4:2-3 warns: “You desire but do not have, so you kill. You covet but cannot get what you want, so you quarrel and fight… because you ask with wrong motives, that you may spend what you get on your pleasures.”

This article introduces a “seeking what not to seek” framework, drawing from science, cultural values, and religious guidance to help us navigate our inherent drive to seek wisely in an information-abundant world—where true fulfillment depends on knowing what not to pursue.

3. How much income should we seek to be happy?

Section 2 examined seeking as an evolution-based catalyst for action. Our genome compels us to seek, ensuring we avoid poverty or danger. We worry about providing for our families or ourselves. Democracy supports citizen-driven seeking, while religions caution against unhealthy forms of it.

In this section, income is viewed as an outcome of seeking. The key questions connecting income to happiness are: “How much income is needed to be happy?” and “Does seeking more income truly improve happiness?” The answers? Less income is needed for happiness than our genome-driven expectations suggest, and more income does not necessarily lead to greater happiness. This section explores these questions in depth.

Psychology and behavioral economics research, notably by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, suggests that once a basic income level is met, additional seeking has a limited impact on happiness. Kahneman’s observation summarizes his findings well: “Money doesn’t buy happiness, but lack of money certainly buys misery.”

If happiness is the goal, then pursuing income beyond a certain threshold may work against it. [i-d]

The happiness income threshold

When do you have enough income?

When do we reach “enough” income? The research, synthesized by Ma and Zhang (2014), presents an income threshold for happiness (based on studies by Kahneman & Deaton 2010, Easterlin & Angelescu 2009, and Inglehart et al. 2008). Yet, our genome, hardwired for social comparison, makes it challenging to settle for an “absolute” income; often, we seek more if others have more, even if it isn’t needed for happiness.

The threshold estimate of $60,000 (in 2010 dollars) serves as an average baseline, although each market varies in cost. The insights are that 1) a specific income level exists beyond which happiness gains significantly drop, and 2) comparative seeking can create the illusion of needing more income than we truly do.

Note on the Minimum Threshold Estimate: The $60,000 figure represents an estimated happiness threshold from Dr. Kahneman's 2010 empirical research, based on average income needs in 2010 dollars. This estimate will vary by market and situation, as inflation has increased since then, and each market has its own cost of living. Individual debt levels also affect how effectively income can be used. Key takeaways are: 1) there is an absolute income level beyond which additional income yields minimal happiness, and 2) due to our tendency for comparative seeking, the actual threshold may be lower than most assume.

Economist Sendhil Mullainathan’s research supports this idea, showing that falling below the minimum income threshold triggers “cognitive tunneling,” narrowing attention and reducing the capacity to think broadly: [i-e1]

“Scarcity in one walk of life means we have less attention, less mind, in the rest of life”

This mental focus on scarcity can crowd out other life priorities. While moderate scarcity may focus goals, extreme scarcity impacts cognitive abilities, restricting the capacity to support others by forcing attention inward toward survival needs. "Budget scarcity" is a common business management tactic intended to focus employees' attention on essential business goals. However, experiencing hyper-scarcity, such as dropping below the minimum income level, alters our cognitive processes and capacity for thinking. It renders us incapable of assisting others as we are focused on securing our own survival. The next graphic shows how tunneling impacts people by income level, where higher income levels are less likely to have large tunnels forcing attention to the short-term, but individual circumstances vary. Life events, such as caring for a sick child, may push someone into a temporary “all hands on deck” cognitive tunnel, making long-term planning nearly impossible until the immediate crisis is resolved. Understanding where someone is in their cognitive tunnel is crucial for setting appropriate expectations and timing for meaningful conversations.

Scarcity and tunneling

Scarcity and Tunneling: A Visual Representation

Regardless of income level, people generally possess similar cognitive capacities. For those below the threshold, “tunneling” shortens their planning horizon, limiting focus on the future or others. Crossing the threshold allows mental freedom, facilitating longer-term planning and helping others. Tunnel width differs per role and family context. For example, in my household, my focus on work balanced my spouse’s broader focus on family, providing joint capacity to support others.

How much income is needed to be happy goes beyond gross income. Especially in the United States, where access to credit is high, people are susceptible to getting into debt trouble. As introduced in the last section, it is natural for people to puff up with debt. Plus, many consumer finance companies will hand people the debt rope to hang themselves.

Someone may have gross income above the minimum threshold but also have soul-crushing debt payments. Those in debt trouble are certainly subject to happiness-reducing scarcity and tunneling. The individual’s debt situation impacts the suggested minimum income threshold.

In summary, a minimum income threshold is crucial but insufficient for happiness. Beyond this level, the additional happiness gained from income declines quickly. Contrary to our genome’s push to seek, the research suggests it’s wiser not to pursue income beyond a certain point. Reaching the threshold provides a platform to help others, as it’s hard to support others when struggling with basic needs. Surprisingly, those who add value often earn more than they seek, as income follows valuable contributions.

As a great paradox, some people earn well beyond their minimum income threshold by focusing on helping others. Consider money as a form of voting: when you create a product or service that offers significant value, people “vote” by choosing to pay for it. In this way, not seeking income for its own sake can ironically lead to an abundance of it.

Next, this article introduces a framework on what not to seek, defining “out-of-bounds” pursuits. Following this, we explore “in-bounds” seeking, providing resources to help readers discern healthy motivations. Seeking to help others is largely positive, while the “NOT” framework addresses our innate but challenging self-focused drives.

4. Seeking by knowing what NOT to seek

Proposing a shift toward activities that bring joy is one thing, but implementing it is a different challenge. Many believe that achieving "enough" - like earning money or achieving work goals, like closing deals or hitting budget targets - boosts happiness. Yet, could the time spent earning or pursuing career milestones be redirected toward activities that help others and lead to greater fulfillment? As shown earlier, the research suggests that the answer is “Yes.” However, our instinctual drive to seek often obscures awareness of alternative pursuits that may better support happiness. [i-e2]

Seeking to Find “Enough”: John Bogle, the late Vanguard founder, shared a story illustrating our struggle with seeking: At a party hosted by a billionaire on Shelter Island, Kurt Vonnegut remarked to Joseph Heller that their host, a hedge fund manager, had made more in one day than Heller had earned from Catch-22 in its entire history. Heller replied, “Yes, but I have something he will never have… enough.” [i-f]

While we are wired to seek more, our genome doesn’t differentiate between resources that enhance happiness and those that don’t. For our genome, happiness is simply survival to pass on DNA; it doesn’t matter how it happens. [i-g] Thus, how and what we seek affects our happiness. Both neuroscience and longstanding religions agree on this point: since our genes don’t discern sources of happiness, cultural support from religion and philosophy fills this gap.

Since knowing what leads to happiness is challenging, the next section introduces a framework with five categories of what not to seek. This framework is grounded in behavioral economics, Stoicism, and world religions. It assumes that achieving a minimum wealth threshold is possible, channeling our natural seeking instincts in line with N.N. Taleb’s concept of via negativa: reaching a goal often begins with understanding what not to do, rather than focusing solely on the end result. [ii-a] This framework provides space to explore joy while using five “NOT” categories as a guide on what to avoid to refine your happiness goals.

Determining what makes you happy is difficult. Instead, aim to avoid what leads to unhappiness, leaving behind what genuinely supports your happiness.

Now, we’ll outline each category in the “NOT to seek” framework. To help you remember, think of seeking “what not to seek” as a way to live well—essentially, to be a “GOOD LIVE-R.” This memory aid highlights five things to avoid seeking:

[L] - Luxury

[I] - Ignorance

[V] - Vanity

[I] - Immediate gratification

[R] - Risk avoidance

“It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor.” — Seneca

1. Not Seeking Luxury: After working diligently, it’s natural to feel we’ve earned some luxury. Yet linking luxury to hard work can be misleading. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle said, “Work is its own reward.” Similarly, labor economist David Autor observed, “Work is what structures adults' lives: it gives us purpose, focus, a set of responsibilities, and an identity.” [ii-a1] This highlights that the intrinsic value of work extends far beyond material rewards. So, why do we chase luxury? It’s often because work enables luxury, and luxury-seeking simply replaces one pursuit (work) with another (consumption). Earnings from work reflect societal value creation, while luxury is how we choose to spend today. With fixed budgets, luxury-seeking often crowds out resources we might otherwise save or use to benefit others. Luxury is thus an inferior substitute for the value we could create by diverting our efforts.

Contentment with what we have fosters happiness. The more we’re satisfied, the more resources—time and money—become available to create value for others and save for the future. This cycle of fulfillment begins by redirecting the very drive that makes us effective at work. Avoiding luxury is also a form of expectation management; as we acquire more, our desire grows, and unmet desires can undermine happiness. By resisting luxury, we selectively pursue “more” that actually enhances happiness.

A ‘Faux Pro’ Bike Example: I recently spoke with a friend who, like me, enjoys biking, though he rides faster and longer, often joining a group of ten riders every weekend.

He had just bought a new bike for $17,000, which surprised me. Curious, I asked why he chose such an expensive model. He highlighted its quality, lightweight, and smooth ride, noting that many in his group also own high-end bikes. People like him are often called “faux pros”—amateurs who, influenced by industry marketing and FOMO, buy professional-grade gear and ride as if they’re pros.

When I asked if he could keep up on his old bike, he admitted he could and that it was not broken; he even kept it as a backup. Given his work as a financial trader, he can easily afford the luxury, but his choice reflects the pull to keep up with the group and ride as if he’s on a pro-like level.

While a less costly bike could meet his exercise and safety needs, his motivations extended to luxury. His bike group became his “Joneses” to keep up with, influenced by a kind of FOMO-driven peer pressure. Assuming he retires in 30 years, the future value of the bike’s price could be nearly $350,000. He is effectively exchanging a faux pro bike for $350,000 that could support him or others in retirement. His choice seems less about utility, like fitness or safety, and more about satisfying the impulse to keep up with peers. Later, we will discuss how appearances often mislead.

The Luxury-Work Dynamic: My friend’s career as a trader, a field that’s competitive and comparison-driven, likely fuels his desire for luxury. The habit of comparing trades and benchmarks translates easily into a “keeping up with the Joneses” mindset. It is challenging to separate work from luxury-seeking, especially when we tend to adopt traits of those around us. So, it is wise to be selective when choosing our influences.

Avoiding luxury also applies the Pareto Principle or the 80/20 rule. Strive for 80% of the value at 20% (or less) of the cost required for the final 20% of the value. The bike example is an extreme case: by not seeking luxury, my friend could achieve nearly all the biking benefits for 1% or less of the long-term opportunity cost.

“Humility is not thinking less of yourself, but thinking of yourself less.”

— C.S. Lewis

2. Not Seeking Vanity: Vanity and luxury-seeking are related, as one’s vanity can drive the pursuit of luxury, but they’re not always linked. Luxury is often easier to assess since it has a price tag. With a bike, for example, you can compare costs and ask whether spending more aligns with your values or simply fuels vanity. Vanity, however, is trickier. For some, self-worth is tied to feeling important—to their workplace, friends, or society. This comes to us naturally, as vanity is connected to Smith's moral philosophy regarding being "lovely." But importance is largely a perception within the mind of the seeker. We tend to inflate our own importance compared to how others see us. Most people focus on their own significance rather than noticing or admiring others’ self-importance. Morgan Housel, author of The Psychology of Money, captures this paradox of vanity:

"There is a paradox here: people tend to want wealth to signal to others that they should be liked and admired. But in reality, those other people often bypass admiring you, not because they don’t think wealth is admirable, but because they use your wealth as a benchmark for their own desire to be liked and admired."

Housel’s paradox traces back to Adam Smith. Writing in the mid-1700s, Smith observed, “Man not only desires to be loved, but to be lovely.” His point was that vanity is woven into human nature. The paradox shows up even in places we assume are purely selfless, such as charitable giving. While generosity may be sincere, it often carries an undercurrent of recognition—names etched on plaques, buildings, or donor lists signaling virtue. In those cases, the gift risks shifting from advancing the cause to securing the image of being charitable.

We should strive to help others and find joy in their company—but without seeking admiration. Demonstrating humility, kindness, and empathy often garners more respect than seeking validation through self-importance.

A recurring theme with vanity and difficult life choices is decision readiness. Choices that impact future growth—like selecting a college or committing to marriage—are challenging because they require envisioning how we’ll thrive in an unknown future. Vanity can cloud our judgment on readiness for such decisions. Listening to your values and consulting people you respect—parents, a mentor, or a trusted community member—can help balance vanity with wise decision-making. [ii-d]

A College Example: Suppose you’re in high school and deciding whether to attend college. Are you ready? You may feel pressure because your “smart” friends are attending prestigious schools, while “losers” choose community college. But that’s vanity speaking! Research shows that peer pressure in college choices often outweighs parental guidance, and it can lead to poor decisions. Questions about study habits and paying fair value for a college education are critical. Community colleges and non-traditional paths can offer substantial value. [ii-e2] Related to Housel’s paradox, the risk is that friends may use your college choices as a benchmark to elevate themselves. Vanity here distracts from understanding how college will support your growth.

“It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so.”

— Mark Twain

3. Not Seeking Ignorance: While people don’t intentionally pursue ignorance, it can easily arise if we aren’t attentive. The phrase “It seemed like a good idea at the time” often signals a choice that, in hindsight, was rooted in ignorance. Ignorance occurs when we either fail to update our beliefs or ignore new information. [iii-a1]

Belief updating requires us to adjust our perspectives as new information becomes available. Philip Tetlock, a professor and forecasting expert, notes, “Beliefs are hypotheses to be tested, not treasures to be guarded.” [iii-a2] However, people often resist testing beliefs, especially when new information challenges long-held views. [iii-b]

To avoid ignorance, we should focus our limited attention on matters that genuinely impact our lives. While gossip about political scandals may be entertaining, unless you’re a policymaker, your attention is better directed toward issues where you can make a real difference. Aim to “Think Globally” but guide your attention by opportunities for “Acting Locally.”

A Deadly Example of Ignorance: The January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, where Americans harmed fellow citizens, illustrates the consequences of unchecked misinformation. A congressional report found that:

“The Committee’s investigation has identified many individuals involved in January 6th who were provoked to act by false information about the 2020 election repeatedly reinforced by legacy and social media.” - 117th Congress Second Session House Report

While the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights protect our freedom to express beliefs, these protections have limits when misinformed beliefs lead to tragic outcomes like the Capitol attack.

“Beware of little expenses; a small leak will sink a great ship.”

— Benjamin Franklin

4. Not Seeking Immediate Gratification: This is one of the tougher “nots” to resist. The availability bias tempts us to satisfy our desires right away, making it challenging to delay gratification. [iii-c] Our personal health and finances are key to long-term well-being, yet our genome complicates efforts to save, eat well, and stay active. To our instincts, saving for the future feels like a small loss in the present. A link at the end of this article provides strategies for managing the pull of immediate gratification.

A Personal Finance Example: As a behavioral economist and personal finance professor, I teach learners to build a consistent, repeatable decision process for a lifetime of sound financial choices. The routine itself is what drives success. This includes habits like “set it and forget it” savings and prioritizing “paying yourself first.” We often use a decision-support app to reinforce these habits; a free version of the app is available with my book.

“If you’re not quitting enough, you’re probably not winning enough.”

— Annie Duke

5. Not Seeking Risk Avoidance: There’s a crucial difference between risk and ruin. [iii-d] Ruin is irreversible—like losing your health, your integrity, or your financial foundation. It should absolutely be avoided. But risk itself is not the enemy. In fact, risks—especially those that are calculated, reversible, and growth-oriented—are essential to learning, progress, and happiness.

Our brains are wired for caution. From an evolutionary standpoint, risk avoidance once kept us alive. But in today’s world, this hardwiring can lead us to avoid opportunities that don’t threaten survival but do offer long-term upside. This includes everything from career shifts and entrepreneurship to meaningful conversations and financial investing.

Take employment, for example. Many people seek jobs with large companies, drawn by perceived stability and steady income. Yet, surveys consistently show that employees at large firms are often disengaged or overworked. [iii-e] In fields like professional services, “greedy work” cultures demand excessive hours with diminishing personal returns. And despite the aura of security, large firms frequently restructure or lay off employees in downturns—revealing that job security is often an illusion.

One strategy for managing this risk is to reframe your career as a portfolio—a collection of roles, skills, and networks rather than a single job identity. Think of yourself not as “the employee,” but as a value creator with multiple channels. Whether you’re freelancing, teaching on the side, or building a startup, this mindset gives you the flexibility to adapt as industries change and personal goals evolve. It shifts your perspective from “the fish” to “the house”—or from being at the mercy of chance to designing your own odds. [iii-f]

Beyond work, this principle applies to health, investing, learning, and relationships. Avoiding emotional risk—like the vulnerability required to build deep connections—can leave us isolated. Avoiding financial risk—like starting to invest—can erode long-term wealth through missed compound growth. Growth comes through strategic exposure, not total avoidance.

As poker champion and decision scientist Annie Duke explains: “Contrary to popular belief, winners quit a lot. That’s how they win.” [iii-g] Learning when to walk away from bad bets—or stale roles—is not failure. It’s progress.

That said, not everyone thrives in high-variability environments. Some find genuine satisfaction in structured, lower-risk settings—such as government, education, or mission-driven nonprofits. If your current path brings joy and aligns with your values, there’s no reason to abandon it. Just be sure it’s a conscious choice, not one driven by fear of the unknown.

The framework identifies five categories NOT to seek. But this raises another question: “What about those who do seek some or all of these NOT categories? How should we view them?”—As long as their actions are lawful, we should accept others pursuing these categories. Adam Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand” describes how people’s diverse moral sentiments converge within a community or marketplace. Smith understood that motivations stem from a complex blend of self-interest, including selfishness and altruism. The invisible hand is an emergent phenomenon because individual and societal situations continually evolve. [iii-g1]

It’s difficult for an observer to fully understand another’s motivations. So even if someone appears to pursue these NOT categories, we may misinterpret their motivations. For example, in employment, a friend may be happy working in a large, structured organization, even if it’s not appealing to you. Why not ask them how they find joy? Or, in the “faux pro” bike case, my friend’s reasons may go beyond what I can see. Just because I value a $500 bike doesn’t mean his choice lacks meaning.

Embracing diversity strengthens the marketplace, enabling it to function optimally. [iii-h] Ultimately, our judgments cause the discomfort. [iv-a] We’re better off valuing differences, following this framework, and withholding judgment. As Southern Baptist minister Billy Graham said:

"... God's job is to judge, and my job is to love."

or as Walt Whitman is often attributed:

"Be curious, not judgemental."

Likewise, we should welcome friends who avoid the NOT categories, surrounding ourselves with people who share positive motivations. However, people’s behaviors shift over time, making it likely they will sometimes pursue a NOT category. Choosing friends who align with these principles is a useful and supportive filter.

My wife and I try to accept our friends as they are, even if their choices diverge from this framework. Our faith emphasizes grace, acceptance, reconciliation, and forgiveness as keys to lasting relationships. We also, albeit imperfectly, measure our own seeking against this framework to guide us in correcting misguided pursuits.

Yet, there are times when releasing a relationship and trusting our faith is the best course. Letting go is never easy.

5. Seeking and not seeking the road to happiness

Our lives are filled with decisions. Many are practical and aimed at boosting productivity, such as those involving education and career choices. Practical decisions are also essential for maximizing the value of income gained from productivity—like personal finance decisions. Yet, the most vital choices impact our contentment and well-being, such as selecting a life partner or nurturing our curiosity. Along this journey, guides help us avoid going out of bounds. They provide direction on what to steer clear of as we approach life’s significant choices.

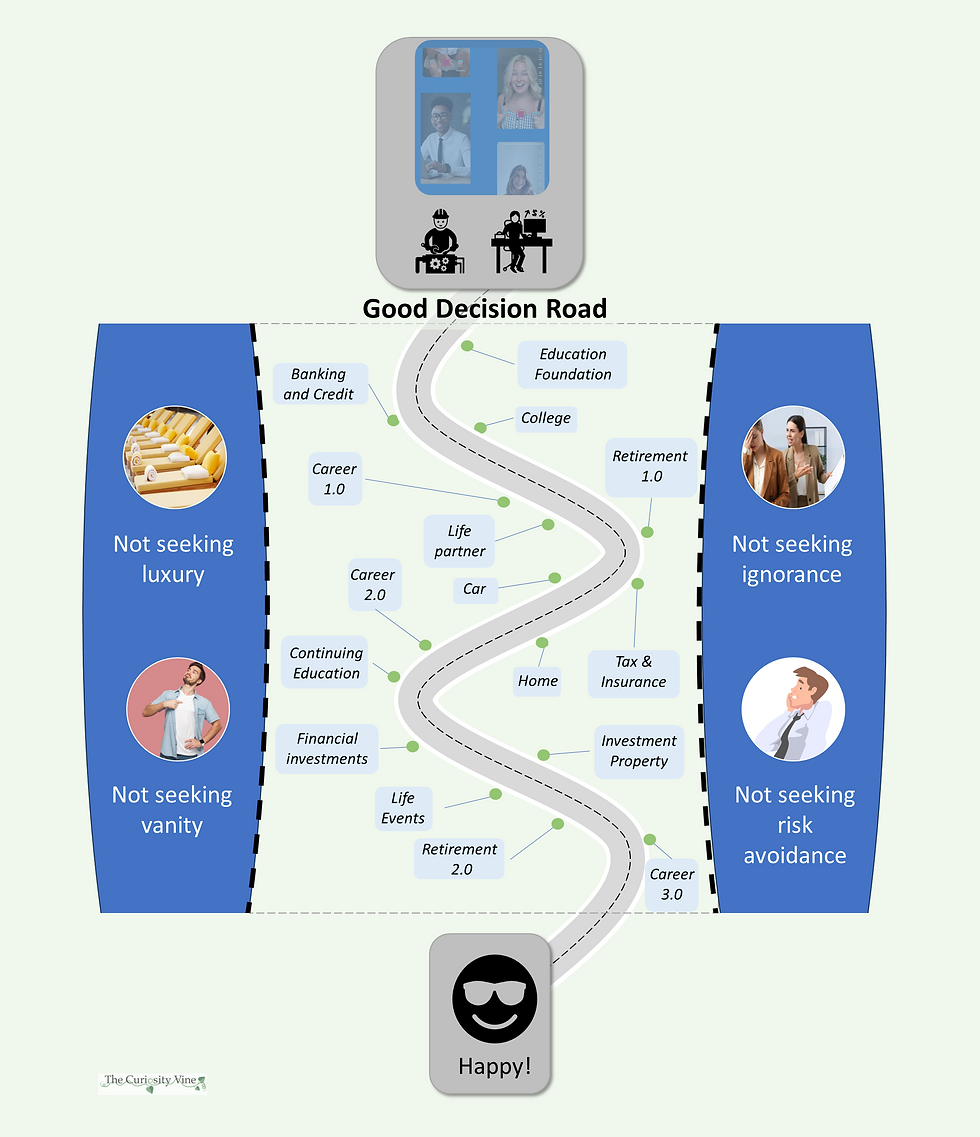

The road to happiness

6. Concluding with the seeking road

We conclude this article with an invitation. The previous graphic highlights many common in-bounds-seeking decisions across education, career, personal finance, and relationships. Explore the tools and content available through the following link to support you in making these decisions. While each decision varies in specifics, they all follow a shared decision framework. In today’s data-abundant world, maintaining a consistent, repeatable decision-making process is more essential than ever.

7. Notes and appendix

Appendix - thoughts on seeking policy

If some struggle with seeking, one might propose laws or government intervention to ensure people “seek correctly.” For instance, the concept of “zero-growth economics” is gaining attention, particularly in Europe, as a policy to curb global environmental emissions. This approach is like using laws to enforce “proper” seeking. While reducing emissions is crucial, trying to control individual seeking behaviors through regulation is misguided. Seeking is deeply personal and often changes over time, making it challenging to regulate. Moreover, the incentives of central policymakers often don’t align with those directly affected by such policies.

This article aims to suggest ways for individuals to manage their seeking. While individuals may not always seek effectively, government efforts to administer seeking-based policies would likely be even less effective. A better approach would be for the government to enable people’s choices in seeking and create an environment that promotes seeking beneficial to society. Think of “law as guardrails,” not “law as Geppetto the puppeteer.” And while I fully support emissions reduction, my Hayekian perspective suggests that government-imposed “zero-growth” policies could ultimately be counterproductive.

Notes

[i-a1] The Liberty Fund edition of The Theory of Moral Sentiments provides detailed commentary on Smith's concept of being "loved" and "lovely," emphasizing its foundation in human social interactions and moral behavior. This edition highlights how Smith connects these desires to the development of mutual respect and societal harmony, illustrating their relevance to both individual happiness and collective well-being.

Smith, Adam. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Edited by D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie, Liberty Fund, 1982 (originally published 1759).

[i-a2] Ryan and Deci's seminal article on self-determination explores the critical role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in fostering intrinsic motivation and enhancing personal and societal well-being.

Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. "Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being." American Psychologist, vol. 55, no. 1, 2000, pp. 68–78.

[i-a3] A study by the San Francisco Federal Reserve reveals that industries with jobs suited for mobile work show higher productivity—a trend already underway before the pandemic. For instance, a call center job is “naturally mobile,” while construction work is “naturally place-based.” This suggests the pandemic served more as an accelerator than the primary driver of mobile work adoption. However, the study doesn’t address whether traditionally non-mobile industries are becoming more open to mobile work post-pandemic, as industry type was a constant in the research. The pandemic certainly advanced mobile productivity technology and raised worker expectations for mobility, indicating that more industries may shift toward mobile-friendly models.

Fernald, Goode, Li, Meisenbacher, Does Working from Home Boost Productivity Growth?, FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-02, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

[i-a4] In summary, the word count of banking laws increased from tens of thousands of words before the financial crisis to several hundred thousand words after the crisis. This is based on an analysis of data from:

Ross, Major Regulations Following the 2008 Financial Crisis, Investopedia, accessed 2024

[i-a5] Hulett, Platform Life: How investors and consumers can survive and thrive in the platform economy, The Curiosity Vine, 2024

[i-a6] Hulett, The case for data after the big change: From data scarcity to data abundance, The Curiosity Vine, 2024

[i-a7] Hulett, Origins of Our Tribal Nature, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[i-b] Levin explores how competition is at the heart of America's constitution and federal governance structure.

[i-c] Wilson (editor), World Scripture, A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts, Section - The Human Condition, p. 293, 1991

[i-d] The shape of the happiness-income curve aligns with the Pareto principle. Within this framework, the Pareto principle implies that roughly 20% of our potential income generates about 80% of our possible happiness. This threshold marks the point where additional income yields diminishing returns on happiness. Beyond this level, pursuing more income provides limited benefit, as the marginal gains in happiness decrease. Therefore, once this income threshold is reached, shifting focus to alternative activities that boost happiness may be more beneficial than continued income generation.

Hulett, Our Trade-off Life: How the 80/20 rule leads to a healthier, wealthier life, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[i-e1] Mullainathan, Shafir, Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, 2013

[i-e2] The challenges to decision-making and solutions to overcome those challenges are explored in the article:

Hulett, Solving the Decision-making Crisis: Making the most of our free will, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[i-f] Housel, The Psychology of Money, 2020

"Enough" has a neurobiological basis. Dopamine is the reward neurotransmitter encouraging the seeking behavior of the hedge fund manager. Serotonin is the satiating counter agent to know when "Enough" has been achieved. In this case, Heller seems to have a better balance of dopamine and serotonin than his hedge fund host.

"But too much dopamine--especially in the absence of satisfaction-inducing serotonin--can lead someone to overindulge in unhealthy or addictive behaviors."

Prat, Chantel. The Neuroscience of You: How Every Brain Is Different and How to Understand Yours. Dutton, 2022.

[i-g] British evolutionary biologist, zoologist, and author Richard Dawkins makes the case for our genomes' singular motivation to pass on our genetic code.

Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, 1976

To be fair, the reasons behind individual decisions extend beyond DNA and genetics. Environment plays a significant role in shaping how our genetic potential unfolds, influencing our DNA’s reproductive opportunities. It also affects our epigenetics—how genes are expressed in response to surroundings. Yet, regardless of the environment we’re “dealt,” our genome is predictably inclined toward self-replication. For further exploration of the interaction between genetics and environment, please see:

Hulett, The Gene Trade: Making the Market for Gene-altering Interventions and Medical Selection, The Curiosity Vine, 2022

[ii-a] Nassim Nicholas Taleb defines "Via Negativa" as, “The principle that we know what is wrong with more clarity than what is right, and that knowledge grows by subtraction. Also, it is easier to know that something is wrong than to find the fix. Actions that remove are more robust than those that add because addition may have unseen, complicated feedback loops.” In other words, "subtraction" or "not doing" is something we can do today with a clear outcome -- which is building capacity to do something else. However, the outcomes associated with "addition" or "doing something else" can take years to emerge. By not doing the wrong things, we create more positive outcome capacity of the things we do to emerge.

Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, 2012

[ii-a1] Autor, David. "Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation." Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 29, no. 3, Summer 2015, pp. 3–30.

[ii-b] Baucells and Sarin cite the fundamental equation of well-being: happiness equals reality minus expectations.

Baucells, Sarin, Engineering Happiness: A New Approach for Building a Joyful Life, 2012

In The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less, Barry Schwartz emphasizes that managing expectations is essential for happiness, as too many choices often inflate expectations and lead to dissatisfaction. Drawing on Herbert Simon’s concept of “satisficing,” Schwartz argues that focusing on good-enough options rather than the perfect choice reduces regret and enhances contentment. This also relates to the Pareto Principle or the 80/20 rule, mentioned earlier.

Schwartz, Barry, The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less, 2004.

[ii-c] See the sympathy modulation framework for how helpers and the helped modulate. Emotion is tempered between individuals.

Hulett, Adam Smith and how choice architecture makes the invisible hand more visible, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

Our tendency to overplay our importance relates to a cognitive bias called self-serving bias.

"The self-serving bias refers to a tendency for people to take personal responsibility for their desirable outcomes yet externalize responsibility for their undesirable outcomes."

Shepperd, Malone, Sweeny, Exploring Causes of the Self-serving Bias, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 895-908, 2008

[ii-d] Hulett, Our Trade-off Life: How the 80/20 rule leads to a healthier, wealthier life, The Curiosity Vine, Section 4d, 2023

[ii-e1] Kelly, PEERS OR PARENTS? STUDY SHOWS STRONG FRIENDSHIPS SET TEENS UP FOR SUCCESS LATER IN LIFE, UVAToday, 2021

Friend groups have a significant impact on teens. In fact, based on a University of Virginia study, friends are often more important than parents as a predictor of long-term outcomes. Separating helpful teen relationships from peer pressure leading to an inappropriate college decision is a difficult judgment. But, given the high number of students who begin college but do not finish college, this judgment frequently ends with college objectives not being met.

[ii-e2] Hulett, Be like Rudy: Community College as a smart, lower-cost path for Higher Ed, The Curiosity Vine, 2021

[iii-a1] Hulett, Achieving the known – how to implement the best information curation framework, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

See Section 3, the HRU framework - The unknown-known (Ignorance or fooling yourself)

[iii-a2] Tetlock, Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, 2015

[iii-b] For a brief tutorial on confirmation bias and reasoning errors, please see:

Hulett, January 6th, 2021, an ignorance example, The Curiosity Vine, 2024

[iii-c] Hulett, Great decision-making and how confidence changes the game, The Curiosity Vine, 2022

[iii-d] "Ergodicity" is the study of the difference between risk and ruin. This article provides a foundation:

Hulett, The Regenerative Life: How to be an ergodic pathfinder, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[iii-e] Hartner, U.S. Employee Engagement Needs a Rebound in 2023, Gallup - workplace, 2023

Hulett, The "Greedy Work" syndrome: Helping the Professional Services Industry solve investment challenges, The Curiosity Vine, 2021

Hulett, How medical system incentives foster an impaired, health-diminished doctoring environment, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[iii-f] Dellanna, Ergodicity: How irreversible outcomes affect long-term performance in work, investing, relationships, sport, and beyond, 2020

[iii-g] Duke, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away, 2022

[iii-g1] Hulett, Jeff. "Adam Smith and How Choice Architecture Makes the Invisible Hand More Visible." The Curiosity Vine, 9 July 2023

[iii-h] Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, 1759

To put a fine point on the "By embracing our diversity, we enable the market to operate effectively" comment. No market is perfect, especially given market participants are flawed human beings. However, as Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek suggests, a market embracing the diversity of its participants is more likely to effectively allocate resources as compared to alternative approaches.

Hulett, A Question Of Choice: Optimizing resource allocation and an HOA example, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[iv-a] Aurelius, Meditations, 180 CE

[iv-b] Billy Graham was an American evangelist, ordained Southern Baptist minister, and civil rights advocate. He said: "It's the Holy Spirit's job to convict, God's job to judge, and my job to love."

A response Billy Graham made after a reporter asked why he attended a rally in support of President Bill Clinton after his sex scandal was made public.

Comments