Our Trade-off Life: How the 80/20 rule leads to a healthier, wealthier life

- Jeff Hulett

- Jul 26, 2023

- 40 min read

Updated: Jul 16, 2024

Trade-offs are the currency of decision-making. The French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778) spoke of trade-offs when he said [i]:

"Perfect is the enemy of good."

We always make trade-offs; sometimes those trade-offs are more obvious and sometimes almost invisible. In the modern decision-making context, decisions are the optimization of multiple "what is important to you or us" criteria. The "best" decision is the alternative that optimizes the weighted criteria. [ii] Rarely, if ever, are all criteria "the best." There are always trade-offs, especially with making healthy choices. The central challenge addressed is that evaluating trade-offs is difficult. In some decision cases, we can only hope to stop evaluating when we are close to a good enough decision. This is an idea that the A.I. theorist and economist Herbert Simon (1916-2001) called "satisficing." Some decisions include difficult-to-evaluate emotions, circular reasoning, and tradeoffs involving the current 'you' for the future 'you.' A generalizable trade-off framework suitable for today's complex decisions is provided. In the business context, a decision-making foundation is furnished.

"Just do it" is a wonderful advertising slogan encouraging achievement. This encourages people to break through barriers and achieve their "perfect" goals. We must be mindful to set ourselves up for "just do it" success. Approaching life through a practical trade-off lens is important for long-term success. A framework and examples with an achievable "just do it" mindset are provided - the framework recognizes that when doing "it" means that we will not be doing something else. We suggest practical tools -- also known as "choice architecture" -- to help make complex decisions consistent, repeatable, and easy. We explore several case studies with various levels of complexity to demonstrate the Pareto framework. Those examples include personal finance, health, an injured loved one, and marriage.

About the author: Jeff Hulett is a behavioral economist and a decision scientist. He is an executive with the Definitive Companies. Jeff teaches personal finance and the decision sciences at James Madison University. Jeff is an author and his latest book is Making Choices, Making Money: Your Guide to Making Confident Financial Decisions. His experience includes senior leadership roles in banking and bank risk consulting. Jeff holds advanced degrees in finance, mathematics, and economics. Jeff and his family live in the Washington D.C. area.

Table of contents:

Introduction

Today, we are not naturally good decision-makers

A Healthy Trade-off: Use the 80/20 rule to set achievable "just do it" objectives

Background

Healthy habits

The business context

Pareto and managing our biggest resources – Time and Attention

Pareto case studies

A personal finance example

Personal health examples

An injured loved one example

A marriage decision example

Conclusion

Resources

Definitive Choice

Definitive Pro

Notes

2. Today, we are not naturally good decision-makers

The operative word in the section title is "naturally." Natural decision deficiencies are identified, along with strategies to help you overcome those deficiencies and become a great decision-maker.

Personal finance and personal health are two examples of important life decisions impacting long-term success. These and other examples share the reality that long-term success occurs decades after high-impact decisions need to be made. [iii] These are particularly complex because they involve time trade-offs. Time trade-offs include the give-up-a-little now to earn a significant pay-off in future decisions. People lack the natural capacity to handle time uncertainty. Our neurobiology, as a result of evolutionary biology fine-tuning, makes us naturally very present-focused. When assessing decision quality, people tend to confuse one’s decision capacity with their decision willingness. "Willingness v. capacity" is explored next.

For tens of thousands of years, your ancestor stayed alive long enough to have a family by successfully acting upon super important, life-sustaining questions like: "Should I run from this lion?" Thus, that present-focused "fight or flight" decision-making capacity was hard-wired into our brains. The decision willingness was habituated by our genetic wiring as an automated response instinct. The willingness to run from the lion does not even feel like a decision - it is a subconscious, instinctual response. It just happens. The fact that you are reading this means that your entire line of ancestors successfully ran from the lion! If only one of your ancestors failed to run before they reproduced the next generation, you would not be here. A chain is only as strong as the weakest link. [iv-a] The part of our brain facilitating this intuitive capacity and feeling-based attention is generally found in the right hemisphere. How our intuition impacts decision-making is explored in the marriage example.

Today, unless there is a jailbreak at the local zoo, we rarely make these sorts of subconscious, binary decisions for survival. Modern laws and medicine have virtually eliminated short-term existential threats. Most modern people can safely live until they are old enough to have children. However, that ancient decision-making wiring is still present in our DNA. We are naturally very good at making mostly unnecessary-for-our-survival decisions.

On the flip side, our brains are NOT wired to intuitively make today's necessary complex, multi-criteria, multi-alternative decisions. Without assistance, this may lead to poor decision outcomes. The decision tools are how we build decision capacity to create and maintain confidence-inspiring decision willingness. Our willingness to act upon a decision is impacted by our confidence in our capacity to make a decision. Capacity and willingness are central to a self-reinforcing decision-making cycle. The more we build our capacity to make a good decision, the more we are willing to act upon those decisions ... and the loop continues. In fact, because our brains are naturally wired to make fast, life-saving decisions, that wiring often works against the slower evaluation process needed for making complex, multi-criteria, multi-alternative decisions. The difference between ancient brain decisions we are naturally good at and modern, difficult complex decisions present as cognitive biases. [iv-b] Our cognitive biases, such as present bias or availability bias, hinder us from properly saving for retirement or from keeping healthy New Year's resolutions. [v] It is our evolutionary biology working against us!

For many complex decisions, our intuition is essential. Intuition presents as our judgment. Judgment sometimes gets a bad rap because it is associated with bias. Consider typical group decisions. An individual has valid judgment to inform the group's decision objective - like "It will help our organization make more sales if we have a better sales system." But that same individual may also have bias impacting that decision - like "Making more sales helps me meet my quota and I have a friend at the sales system vendor." If you are the organization's primary decision-maker, like the CEO, or the organization's decision process leader, like the CTO, you worry about the decision stakeholders' judgments. Are they motivated by what is best for the organization, or themselves, or some variation of both? Even if judgments are selfishly motivated, does it matter? As long as selfish motivations are aligned with the organization's positive outcome. It is difficult to know.

The good news is -- with the use of choice architecture tools -- it is possible to tease out our "good" judgment from the bias. Judgment and intuition are important. It fills in the blanks to best inform risk and strategic objectives difficult to quantify. Just before the article's conclusion, health, wealth, and other more typical examples are explored. Some are simpler decisions - like how to best handle high debt levels. Others are more challenging decisions - like the marriage example, where our intuition is essential to handle computationally challenging self-referential evaluations. But almost all decisions will benefit from using this trade-off-enabling approach. But first, we will set the table by describing the Pareto Principle framework.

3. A Healthy Trade-off: Use the 80/20 rule to set achievable "just do it" objectives

a. Pareto Principle Background

Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) was an Italian economist. [vi] He introduced the concept of the Pareto Principle, otherwise known as the 80/20 rule. Think of the Pareto Principle as a framework for today's common trade-offs. This started in the social sciences and economics context. Pareto demonstrated there was a consistent, repeatable relationship between population and wealth. In 19th-century Europe, approximately 20% of the population owned about 80% of the land. This non-linear "power law" concept is regularly observed in many social systems.

The Pareto Principle in action: In the business context, often "80% of sales come from 20% of the clients" or "almost 80% of the clients use 20% of a company's products." In the criminal justice context, "20% of criminals commit 80% of crimes." There is no shortage of examples demonstrating the Pareto Principle in action.

Sports are also impacted by the Pareto principle.

Baseball and the Pareto Principle. According to the Baseball Almanac and Major League Baseball, the 2022 league batting average was .243. This means the hitter was successful about 24% of the time. In 2022, 70% of batters achieved at least a .243 batting average. This represents an almost 80/20 split -- where 70% of players achieve average batting success about 24% of the time. Baseball's governing body did not calculate the best baseball rules to achieve this (almost) 80/20 rule. In the case of baseball, competitive rules like salary caps, pitching rules, bat requirements, etc. evolved. The rules became a competitive trade-off environment that optimized the outcomes for all baseball parties based on their collective trade-offs. Like in the case of the Adam Smith-inspired invisible hand market environment, the trade between the market participants looks like this:

- The players trade their baseball skills to make income and enjoy a team sport,

- The owners trade their capital and baseball knowledge to make income and enjoy running a sports business, and

- The fans trade their income to be entertained and enjoy a team sport.

The balance of participant investments - like player skill, owner capital, and fan income - plus baseball's rules provide a win for all. Alternatively, if one of the participants did not have a winning outcome, the market itself would not exist. The essential point is that the Pareto Principle is the typical outcome of a stable market when a balance of acceptable benefits has been reached for all market participants.

In the Pareto context, "stable" is defined as a large, reasonably competitive market, where market agents are free to enter, exit, and make decisions to optimize their incentive set. The rules governing the market are known to the participating agents ex-ante. If a market does not exhibit Pareto Principle outcomes, it is likely because one or more of the stability definitions has been violated.

The Pareto Principle, while not always exactly 80/20, is a great rule of thumb to apply to many human behavior situations requiring trade-offs. In the not-as-exacting social sciences and human behavior, the Pareto Principle is analogous to mathematical constants like Pi or e.

The Pareto Principle operating thesis -- when people, also known as participating agents, can choose their trade-offs within a stable system, the individual trade-offs will aggregate to converge on an 80/20 system outcome.

b. Pareto Principle and Healthy Habits

The baseball example is a macro example describing behaviors and outcomes between aggregations of individuals. Those aggregations are categorized into participating groups - such as players, owners, and fans. But what about the individual or the micro? As considered next, the individuals aggregating into those participating groups also exhibit Pareto-like 80/20 outcomes. For groups, the Pareto outcome results from the dynamic balancing between more extrinsically-focused benefits and costs of the participating groups. For example - a ticket price is the external money cost charged to a group of fans. For individuals, it is the dynamic balancing between more intrinsically-focused benefits and their ability to comply with achieving those benefits. For example - someone's ability to pay down debt is from an individual's internal motivation. While the focus may differ between the macro and micro, both still resolve to Pareto-like 80/20 outcomes.

Healthy habits are explored as an individual application of the Pareto Principle.

In the case of healthy habits, we want to avoid bad habits. But then the question becomes "What healthy habits should we seek?" We have choices about how to implement healthy habits. Just look at a typical New Year's resolutions list, along with the percentage of total survey respondents choosing each resolution:

Improved mental health (45%)

Improved fitness (39%)

Lose weight (37%)

Improved diet (33%)

Improved finances (30%)

Courtesy of Forbes Magazine

A common mistake is when people initiate the "perfect" or "best" diet or the "most rigorous" exercise routine or savings and investment program. The problem is that those "bests" often have higher rates of non-compliance. [vii] That is, people will start with great intentions, but discontinue the great healthy behavior and return to the bad habit. On average, people do not stick with their New Year's resolutions. As in the earlier baseball example, think of baseball fans deciding whether to go to an upcoming home game similar to your exercise benefits and ability to attend to those healthy exercises. They all involve life trade-offs. Non-compliance with healthy habits is a big challenge. In decision-making, deriving value from a healthy lifestyle change is a TRADE-OFF with compliance with the healthy lifestyle change. Think of the trade as the current you for the future you.

Example: Trading the current you for the future you.

Today, you could blow off working out for something more fun.

Score: Current you = 1, Future you = 0.

Alternatively, you could keep the workout commitment instead of doing something more fun.

Score: Current you = 0, Future you = 1.

The magical "good" habit math is when something you initially did not want to do but is good for you to do becomes a habit, then not doing the good thing feels like a current loss.

Score: Current you = 1, Future you = 1.

An Aristotelean principle is that "We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit." So what would Pareto do? Pareto suggests there is an in-between point between bad and great.... this is a good habit. Good habits are where you achieve 80% of the benefit, but are much more likely to stay compliant. When pursuing healthy habits, it helps to start with good habits that fall into your "more likely to comply" category. Then, you can move to an even better habit over time once you establish the "good" baseline. The Pareto approach is a process for achieving Aristotelian excellence.

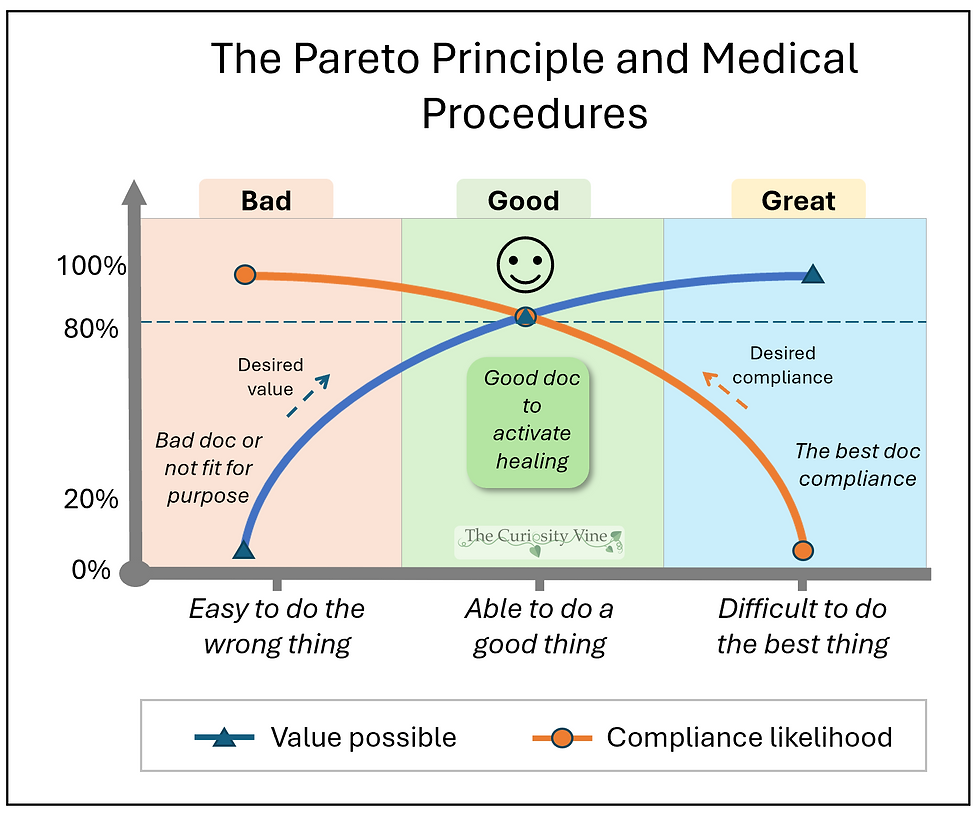

Let's walk through the diagram:

Determine the expected value: In the previous diagram, notice the non-linear, Pareto-like nature of the "Bad - Good - Great" group descriptions along the horizontal desired outcome dimension. By multiplying the percent of value received by the probability of compliance, the expected value for each group is estimated.

Great

While "Great" provides an opportunity to achieve 100% of the value, you have a low chance of achieving that value.

(Under the "Great" tab, the blue value triangle is higher at almost 100%. However, compliance with the "Great", as shown by the orange circle, is only about a 20% probability.

As such - a 100% valuable program times only a 20% chance of compliance approaches 20% expected value)

Bad

"Bad" is at the other end of the spectrum. "Bad" is easy to achieve but provides almost no health value. This may be the current state you wish to change.

(Under the "Bad" tab, the blue value triangle is almost zero. There is an almost 100% probability, as shown by the orange circle, of achieving that bad outcome.

As such - an almost 0% valuable program times an almost 100% chance of compliance approaches 0% expected value)

Good

The optimal point is "Good," where you achieve 80% of the value at a much higher 80% chance of compliance and developing long-term healthy habits. "Good" is often superior to "Great" because of the non-linear nature of how more likely we are to comply with "Good."

(Under the "Good" tab, the blue value triangle is 80% times an 80% chance of compliance shown in the orange circle is a higher 64% expected value)

Decisions at the margin: In the economics world, moving from good to great often runs into a value optimization challenge. Economists view the world through the marginal cost and marginal benefit lenses. To optimize value, the marginal benefit must be greater than the marginal cost.

Bad to good = Yes: Going from bad to good, the marginal benefit is greater than the marginal cost. (80% marginal benefit > 20% marginal cost or chance of not complying)

Good to Great = No: However, moving from good to great often runs the risk that the marginal benefit is smaller than the marginal cost of achieving that marginal benefit. (20% marginal benefit < 80% marginal cost or chance of not complying)

The following is a graphical summary of the Pareto Principle outcomes on many life decisions:

Thus, in the typical Pareto Principle model, good is the optimal stopping point. [viii-a]

Bad, Good, or Great is user-defined: How each of us defines Bad, Good, or Great plus our individual compliance discipline is intensely personal. "Great" to one person may only be "good" for another person. So, our definition of what constitutes bad, good, and great may differ. There are some people with a high likelihood of implementing a great solution. Since people have many different activities to prioritize - like personal health personal and finance, another consideration is the importance of that activity. High-importance activities may get more of your attention, thus, making it more likely to comply. In the marriage example discussed later in the article, "motivation" is showcased as an essential driver of whether to marry. Being honest about your ability to attend to a life activity is essential to achieve a great outcome! Behavioral science teaches us that less salient activities, such as the health and wealth examples, are notoriously difficult for most people to prioritize. A good outcome is SO much better than a bad one! [viii-b]

The minority rule: All rules are likely to have exceptions. The Pareto Principle is no different. The minority rule is an exception case where small communities persist in implementing 'great' in the context of the 'good.' The minority rule is where a small percentage of highly motivated people assert their preferences over a much larger majority. A good example is the food industry’s willingness to certify their food as kosher. A very small percentage of the population applies strict kosher principles to their food choices. However, because of a highly focused effort by the Kosher, Rabbi-led community, many commonly available foods are evaluated and certified as kosher.

This is an example of the Pareto principle-based interactions between multiple parties. This starts when a small community decides to assert their preferences, like a food choice, in their great category. In this case, it is motivated by moral, religious-based principles. Because they were motivated and felt morally obligated, this small moral community could comply. Thus, in the limit, this small moral community is achieving 100% benefit AND 100% compliance. So, their expected value in the great category is at or near 100%, less any transaction costs.

But what about the other 99% or so of the remaining population that do not really care about being kosher? This is where it gets interesting. To a kosher-insensitive person, kosher foods are not that different than other foods we normally eat. Also, many are more likely to put food in our good category.

Most people do not consider their food choices as a moral commitment in the way a strict kosher person does. Non-kosher obligated people can achieve good and eat kosher. Also, the cost difference is not noticeable, so compliance with either kosher or non-kosher foods is similarly achievable. So - the non-kosher group is achieving the same expected value (about 64%) when eating kosher or non-kosher food.

As such, non-kosher people do not really care either way, so many in the food industry take the extra step to certify their food as Kosher to satisfy a very small population. This certainly did not happen overnight. Over time, especially as food industry decision-makers came to be sympathetic to the kosher moral cause, they added kosher certification to their food process and labels. Also, the original cost to the moral community to achieve 100% compliance was not insignificant. However, today the marginal cost of compliance likely approaches 0, as the moral community has achieved a self-complying kosher standard in the broader community.

The minority rule

The renormalization of the majority group by a minority group.

c. The business context:

Some business leaders may wish to go from "Good to Great." Jim Collins, the author of the book of the same name, certainly thinks so. The business world is constantly faced with trade-offs. As a business grows, there are always more ideas for projects than there are resources to implement them. Business decision criteria and project alternatives are always in need of trade-offs. The point is to be hyper-clear about business strategic objectives. The most strategic business driver alternatives should be prioritized. Do most strategic alternatives reach "great" when first implemented? No. But over time, they may reach "great" or "great-ish' with ongoing focus. However, there are many business alternatives that are necessary but less strategic. These are important to stop at "good" and divert resources to other strategic projects.

Let's face it, the world is ever-changing. Perhaps a project that was originally viewed as highly strategic. Over time, the project either:

Turns out to be far more difficult to achieve that strategic objective than originally thought, or

The project is far less strategic today than when it was begun.

In the resource section, process tools are suggested to help evaluate the degree to which project alternatives are strategic, and, processes to help businesses adapt as the business environment changes.

d. Pareto and managing our biggest resources – Time and Attention:

People naturally think of resources like income or savings as their source of wealth.

Not so.

Income and savings are an outcome of how each of us invested two very important assets. These personal assets are something we all have in common.

Our essential investable assets are Time and Attention. The challenge is that not everyone recognizes, develops, and deploys their time and attention as an investable asset. In the context of the 80/20 rule, how we deploy our time and attention to make those regular investments could lead to a flourishing or undesired outcome. The point is, we all have about 170 hours in a week. Most of us have a base of mental capacity to achieve a fulfilling life. Achieving fulfillment occurs when we deploy our mental endowment to attend to our time investments.

A Time and Attention investment example: In my Personal Finance class at James Madison University, I showed the learners the modeled path for achieving $16 million for retirement. I use reasonable savings rates, income growth rates, and investment return assumptions. I also let them know, this is based on the average income earned by a JMU graduate. Also, importantly, I let them know this assumes they have no family inheritance. The $16 million is only based on their savings capacity. The point is, all of them can achieve a healthy retirement. However, it will only occur if they deploy their time and attention over 40 years to achieve that wealth outcome.

Some suggest that people have a pre-determined life path based on their genes and their childhood upbringing. There is some truth to this. We are all certainly impacted by our genes and environment. However, we still have choices about how we deploy our time and attention. We can change, become who we wish to be, and lead a flourishing life. The determinist folks are correct in that, because of our genetic and environmental heritage, it is more challenging for some people than others to make those time and attention investments. While the past is fixed and the future contains uncertainty, we all can make a good choice in the current decision moment.

"Today is only one day in all the days that will ever be. But what will happen in all the other days that ever come can depend on what you do today."

- Ernest Hemmingway

Pareto has much to say about this. The Pareto Principle is about attending to the good habits, knowing when to go on to the other good habits, and avoiding or changing bad habits. The Pareto Principle helps us deploy our valuable time and attention. Pareto helps us choose well NOW.

To explore our Time and Attention investment opportunity, please see:

Next, Pareto Principle case study examples are provided. These case studies are presented in a personal context to maximize understanding. There is a short conceptual bridge from these personal cases to the business world. They may certainly be considered conceptually relevant to the business world.

4. Pareto case studies

a. A personal finance example

We all intend to keep debt under control. However, some people find themselves in situations where they have too much, high interest-rate debt. If you find yourself in debt trouble, there are choices for how to reduce that debt.

The “Great” debt repayment solution and what some economists would call most rational is 1) ranking your debts from highest interest rate to lowest interest rate and 2) starting to repay with the highest interest rate first. This is the most rational because it is the highest interest rate that causes the highest relative expense. So, a great solution is to pay that debt first.

You are probably already asking the right question. “What about compliance?! How likely is the debtor to repay this way?” You are correct to question! Crushing debt is psychologically challenging. The person is feeling significant resource scarcity pressure that creates a challenging-to-comply environment called tunneling. [ix] Non-compliance with the debt repayment program is a valid concern potentially leading to bankruptcy.

The “Good” debt repayment program is one that increases the chances of compliance. Personal finance personality Dave Ramsey recognizes that people run the risk of being rational but non-compliant. As such, Ramsey recommends the "debt snowball" method to extinguish the debt. [x] The debt snowball method focuses repayment energy on extinguishing the smallest balance debt first. In Ramsey's method, creating positive debt payment momentum and confidence is more likely to give you motivation and will help you finish your debt repayment journey. The debt snowball method may not be mathematically optimal compared to paying the highest interest rate debt first. However, it will be more effective from a behavior change standpoint. Less rational and more compliant is certainly a positive outcome! By the way, an achievable “Good” debt repayment program is consistent with the behavioral economics-promoted "commitment device." A repayment approach encouraging commitment or compliance is a good thing!

Upon building confidence and making repayment a habit, the debtor may certainly switch to the great method and pay higher interest rate debt first. But notice, we started with the good method to ensure compliance.

b. Personal health examples

Weight loss challenge

I have friends who work in the capital markets group at Fannie Mae. Every year, the team has a weight loss challenge. Presumably, Fannie Mae’s trading environment does not always encourage healthy life behaviors. The challenge is a way to remind employees of the importance of leading healthy lives.

The challenge starts as well intended awareness to watch our weight. The trouble starts with the challenge time frame. The person who wins is the person who loses the most weight in a relatively short period. This means that the winning behavior includes going on fast, high-impact, but more likely to be unsustainable diets. With a group of super competitive bond traders, the peer pressure to quickly lose weight and show results is palpable. This “big loser” mentality falls in a short-term “great” category.

The result of the challenge encourages unhealthy weight whipsawing. If someone loses weight too quickly, their body is more likely to interpret this as a starvation threat and encourage binge eating to compensate. This is a natural part of our evolutionary biology. Thus, the chance of weight-loss compliance is much lower in this great category. A better approach is to build long-term, sustainable eating and healthy habits to maintain the desired weight. Slow and sustainable weight loss is far better than fast and more likely to whipsaw. This “good” approach may not win the short-term “biggest loser” award, but the good result is more likely to lead to long-term, sustainable health.

Smoothie

Smoothies can be a staple of your morning nutrition routine. For a variety of reasons and with the proper multi-nutrient recipe, they are very good for you. The biggest challenge with smoothies is to minimize sugar. Fruit is often a core smoothie ingredient. Raw fruit has natural sugar called fructose. But other ingredients, like orange juice and yogurt, may have excess sugar additives, which are helpful to avoid. I suggest people start with smoothies with a level of sweetness that tastes great. Liking the taste of the smoothie from Day 1 will greatly improve the chances that the smoothie breakfast will become a habit. It may start with higher levels of added sugars. But this still falls in the "good" category compared to breakfast with fatty and difficult-to-digest breakfast meat, sugar-additive cereals, and carbohydrates. However, over time and once the smoothie habit is routinized, you can slowly reduce sugars.

This is how you move from good to great. Notice, we did NOT start at great. As the smoothie habit builds, it will make it easier to move up the value curve to the slightly less tasty, lower-sugar smoothie. In fact, over time, you will start to develop a taste for less sweetness... which is a great thing! I call this habit-building approach to health: "Boil Your Own Frog" Please check out the citation for details about my smoothie recipe and approach to boiling your frog! [xi]

Healthy habits, like finances, diets, and exercise programs are very faddy. Many fads seem to come and go. There are many companies seeking to help you achieve health goals with their "best" system. People are naturally drawn toward the "best." Often, unfortunately, at the cost of other "good" alternatives. Most importantly: DO WHAT WORKS FOR YOU TO ACHIEVE LONG-TERM HEALTH. Health, whether financial, body, or mind, may be achieved with a portfolio of good alternatives. Making health a habit should be your first priority, not the "best" this or that health program.

Many people struggle with stopping at good. People naturally desire to reach great. In the timeless words of the 19th-century economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen, he said:

“Invention is the mother of necessity.”

Read this quote again -- the words, “necessity” and “invention” are in the reverse order of what you may expect. Veblen’s pithy word reversal reminds us that people are naturally insatiable. Stopping at good is very difficult for most people. [xii] The decision process, called "choice architecture," is an essential ally to achieving the best decisions. In the following resource section are examples of easy-to-use tools to achieve health and wealth in your personal and business life.

c. An injured loved one example

When it comes to Pareto thinking, the rubber hits the road when it comes to medical procedure decisions. Pareto thinking is all well and good until intense emotions impact our decision-making. Medical procedure decisions involving loved ones is when you find out whether Pareto thinking has been truly internalized.

Imagine a loved one, like a close family member, is in a car accident. They are injured and need surgery. It is a significant injury where time is not a friend. The longer we wait, the higher the risk of a bad outcome. If you are the responsible family member, like a parent, your priority response is likely to:

Do a deep dive into the Google or GPT rabbit hole to drain available knowledge on the particular injury,

Interview medical professionals and others to gather information.

Seek out the best surgeon possible to perform the surgery.

You may already anticipate how the Pareto thinking could impact this typical priority response. The first 2 priorities make sense. Good decisions are born from curated information. The 3rd ‘best’ surgeon priority is where we need to flex our Pareto muscles.

The best surgeons are more likely to cost you time and money. Time – because the surgery may need to be delayed until the “best” surgeon is available. Since ‘time is not your friend’ – a time cost increases risk. The financial cost of the best surgeon may be significant. If they are out of your insurance network, their cost may be much higher than an in-network surgeon. What if the patient does not have insurance? Also, if the ‘best’ surgeon is out of the area, the transportation and other logistical costs may be significant.

Your first response may be – “Health is too important! Only the best for my loved one!” Ok, let’s test that response:

Let’s say there are 3 kinds of surgeons

Bad surgeons → inexperienced or surgeons with spotty records.

Good surgeons → competent surgeons with a variety of related experience and good outcomes.

Best surgeons → stellar reputation, wrote the ‘book’ on the surgery, wins awards, etc.

The human body, especially of younger people, is very regenerative. Most people are fulsome healers. As such, surgery should be performed that activates the patient’s healing powers. Thus, the surgery outcome needs to position the patient to heal. The body will do much of the healing heavy lifting. So if both a good and a great surgeon position the patient to heal, they may be equivalent relative to the expected patient outcome.

Every medical situation is different. Emotions have a tremendous impact on the medical decision process. Emotions contain judgment. Emotions also contain bias.

For example, fear does provide information content. "If my loved one does not get surgery soon, they may die!" A feeling of fear signals potential risk in the future. Unfortunately, fear is a blunt signaling device. Fear does not properly evaluate the significance of the risk. As such, fear may create bias because we may under- or overreact to the level of risk signaled by fear.

The essential point is to separate the good judgment from the unwanted bias. Use fear or other emotions to motivate quick evaluation but NOT to make the decision itself. To properly evaluate emotion, an 80/20 way to approach a significant health decision is to:

Inform yourself as suggested in priority 1&2 earlier.

Share your learnings with the decision team.

Clearly define your decision benefit criteria, risk criteria, and costs, such as:

Psychological pain tolerance of the patient (how long can the patient withstand the pain)

Aside from the pain impact, patient outcome risk scaled over time (short/medium/long time). That is, what are the probabilistic outcomes (positive or negative) and what is the likely timing of those outcomes?

Quality of the surgeon and medical team (Good or Great). Since bad surgeons will likely be filtered out as a viable alternative, this criteria should isolate the weighting of going from good to great.

Availability of Surgeon (short/medium/long)

Cost and insurance coverage for surgeons and related treatment costs.

There may be other criteria and costs… this list should be tailored to your situation.

Weight the criteria. This is good to do with other responsible family members, the patient (if able), and a situationally independent hospital administrator. As a best practice, the surgeons should be consulted as information input to the decision but likely should not directly influence the decision model or alternative scoring. Hammers - the surgeons - are biased toward choosing nails - the surgery.

Apply the criteria to each surgeon and treatment alternative.

As discussed in the resource section, apps like Definitive Choice help with this decision-making process.

Once your criteria are clearly defined and weighted, the best surgery alternative will reveal itself as the surgeon alternatives are evaluated. The Pareto trade-off magic happens in the weighting. Decision science tools like Definitive Choice have the process to help patient decision teams make a fast, accurate, and confidence-inspiring decision. Attempting to weigh the criteria and alternatives without assistance is challenging, if not impossible. As discussed in Section 2, our brains are not geared toward complex, multi-criteria, multi-alternative decisions. On top of our natural decision challenges, the addition of the emotions we feel for our loved ones causes even bigger decision challenges. Since the many 80/20 tradeoffs are handled in the app, the final decision recommendation is likely to be Pareto-inspired and accurate!

The importance of your medical decision team.

A challenge of this decision is that you are making it for someone else you love. If you choose the good medical path and the person dies or has an undesired outcome, you will feel horrible. Not just because you lost a loved one, but because you may have a nagging feeling you should have chosen a different medical path. Real life does not come with a control group. That nagging feeling is a form of "buyer's remorse." This is where our subconscious does not fully process a decision and, after fuller processing, is raising emotional red flags.

There is typically a point person to make the final call. That person may feel lonely and overwhelmed by the emotions of the moment. Engaging your decision team helps engage the "wisdom of the crowd" and ensures everyone feels they have input into the decision. Also, using the decision technology will record and balance everyone’s input fairly. Ultimately, you and your decision team will be able to confidently say: “We made the best decision we could given all the information available at the time.“ Your loved one could not ask for more! For the point person, while losing a loved one will not be easy, at least the potential regret of not choosing differently will be reduced via decision confidence. Using a robust decision process will greatly reduce the chance of buyer's remorse-related psychological feedback. Effectively, your subconscious will be fully "heard" via the decision process.

Finally, if sordid wrongful death questions or lawsuits are made by Monday morning quarterbacks, a full accounting of the decision process is an available by-product of a disciplined decision process.

The injured loved one example demonstrates the potential for more challenging decisions. These are decisions where the impact of decisions made in the present impact who you become in the future. For example, if the loved one is a parent, how will the aftermath of the procedure impact how you flourish in the future? In the case of a mature, adult child deciding on behalf of a senior adult, the medical procedure's future flourish impact may be relatively small. However, the next example discusses marriage as a significant future flourish-impacting example.

d. A marriage decision example

This is a different kind of decision. The marriage decision is among a set of decisions that economist Russ Roberts calls “Wild Problems.” [xiii-a] This means that deciding whether to marry is difficult to reduce to a decision algorithm. We will explore what makes the marriage decision a wild problem challenge, we will separate the “whether to marry” from the “who to marry” questions, then, we will explore how to apply the Pareto framework.

The decision of whether to marry can be challenging. Some may have concerns about reducing their time to do other stuff, like work or play. I call this "FOMO opportunity cost." Also, some people's childhood experiences may have discouraged them from having children of their own. For me, I just listened to my culture, my religion, my parents, my genome – which presents as my libido or hormones – and even the U.S. Tax code. All these respected sources encouraged me to be married and have children. [xiii-b] My memories of childhood are great. I had two caring parents and 3 siblings to share our childhood together. I was fortunate to have these "listening" resources when I was a child.

When I was in my twenties, marriage seemed like a natural and obvious next step. FOMO opportunity cost was not much of a concern for me and my memories of family and marriage were positive. My outcome has been a blessing. I am fortunate with an amazing life partner of over 30 years and 4 successful adult children. However, for others, the decision of whether to marry may not be as obvious. I was lucky. The decision to marry is not obvious to many.

One of the reasons the “whether to marry” question is not so obvious is that it is a notoriously challenging two-way internal question. The two-way nature of the question creates a self-referential paradox. Before exploring the challenges of the internal question, first, the more straightforward one-way external question is summarized. Many decision questions do not have as intensely an internal component as marriage. Think of personal finance questions involving a car, a house, a retirement plan, and a checking account. Those are mostly external to you questions. This means that the benefits derived from the decision criteria are external to you. As such, your view of your benefit is a one-way street - viewing from the inside of your brain to learn of the benefits contained in an external criterion. For a car-buying example, suppose you are looking for a fast car, a blue car, an electric car, and a car with a great music system. In that case, the benefits achieved from those criteria are external to you. In the decision-making context, external one-way criteria are able to be directly weighed and evaluated, especially with the help of choice architecture. The degree to which your criteria are one-way external or two-way internal is on a spectrum and one-way external benefit criteria characterize the more straightforward decisions.

Whether to marry

Whether to marry is different. It is a two-way internal question. If you marry, your life will change. Certainly, in my case, my wife and I adapted to each other and our environment over time. It was our willingness to adapt that made our marriage work. The very basis for evaluating “what is important to me” criteria will adapt over time to become more like the person you marry. You cannot help but be influenced by the company you keep. Over time, two-way criteria loops back to impact how you evaluate the criteria. Your personality and standard for evaluation will evolve.

The basis for this internal challenge is what mathematicians call self-reference. It starts with evaluating something from the outside to how it benefits you on the inside. This is fine and is similar to the external question. However, with internal questions, you are found within that being evaluated. People naturally create mental maps of what they expect the future to be like. The two-way challenge is that the map of the future contains you and you are holding the same map! The inside “you” needs to anticipate how being married will impact the outside “you” of the future. Then, that future outside “you” needs to have a view back to the inside “you” to put it in the context of that being evaluated. It creates a recursive loop that never ends… or doesn’t end until you exhaust or frustrate yourself! It is like a dog chasing their tale. The great logician Kurt Goedel famously proved this challenge with the “Incompleteness Theorem” for related undecidable mathematical problems. People decide to get married all the time, so these challenging self-referential problems are decidable. However, they are not decidable with traditional algorithms. In the context of Pareto, knowing when “good” has been reached is essential for knowing when to stop iterating that recursive loop.

Finally, the question of “whether to marry” may be more of a question of the degree to which someone is ready yet to marry. So, the person suspects they want to be married or have children, but that internal messaging system – like culture, religion, parents, genome, etc. - has not yet kicked in. For our purposes, we will treat “whether ready” or “whether ready yet” as similar internal challenges that can be rolled up to the word “motivation.” That is, how internally motivated are you to be married? Do you feel it today? Do you anticipate feeling it soon? Roberts, the economist mentioned earlier, provides a helpful metaphor. He relates the "whether to marry" part of the decision as your motivation to "flourish" or your process of "becoming." Marriage is certainly not the only way to flourish, but history teaches us that marriage is an important path to flourish.

The ”whether to marry” question is found in the blue triangle “value possible” part of the Pareto framework. Once you feel like you are somewhat close or “good” for being married, you have traveled up 80% of the curve and it is worth stopping at this point. This means, stopping to determine “whether to marry” and shifting into “who you should marry” mode. In general, it is assumed a) most people wish to have children, and b) having children is facilitated via the marriage institution. The reason for the “wish to have children” assumption relates to our genome. In his landmark book, “The Selfish Gene,” Richard Dawkins makes the case for how our own genome is the source of our desire to reproduce. Dawkins reduces the magic of love and marriage to a naturally occurring biological outcome driven by our genomes’ incentive to replicate our DNA. [xiv]

Notice, the word “feelings” is the description of how to evaluate whether to marry. These are very much internal feelings-based information and not external objective-based information. People may misunderstand feelings. Our feelings are important information, especially to resolve the two-way internal paradox. Albert Einstein is widely believed to have said:

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant.”

For the marriage decision, it is the “intuitive mind” containing those needed feelings to reveal whether to marry.

But instead of 1s and 0s, like objective data, internal information is presented as feelings. The source of a loving feeling may be your genome saying - "Yep, it is time to reproduce!" Whether or not the object of that feeling - your suitor - is intended or coincidental is another question. While our choice of spouse may feel like it was fated to be, personally, I suspect it is much more random than we think. What are the chances that both your readiness and who to marry criteria path will intersect with another’s at the perfect time? Why them and not another's path?

Because there is no explicit language to a feeling emerging from our neurobiology, they present as vague blobs of information that must be interpreted. It takes work and commitment to interpret the emotion blobs!

One may believe that those more “intelligent” maybe less likely to make biased decisions. This may or may NOT be true. Our propensity to make biased decisions starts with defining intelligence. Interpreting our blob of emotion informs our intuition and judgment. This is an important kind of intelligence, especially when the future is uncertain. Cognitive processing speed, language, and breadth of memory is a very different form of intelligence.

Because of language, some may allow their cognitive intelligence to overpower, effectively drown out, their emotional intelligence. Learning to respect and balance our and others varying intelligences is the hallmark of a great decision-maker. As a result, someone that presents as intelligent because of cognitive intelligence may still make biased decisions. This may occur if they fail to properly weigh their emotion-based intelligence. Others may be swayed by cognitive intelligence of another because they seem so sure of themselves. [xiii-c]

Please see the “Brain Model” for more information about how the different hemispheres of our brain interact to process both kinds of information. Also, the use of smartphone decision tools, like Definitive Choice, helps to separate good judgment-based emotion from confidence-reducing bias or noise. [xiii-d]

Some cultures handle the self-referential challenge via some degree of arranged marriages. As we will discuss next, there is some wisdom in helping younger people with cultural rules to offset this challenge. Presumably, the wisdom of the older generation includes the ability to resolve self-referential decision challenges. Arranged marriages are like the original match-making platform such as Match.com.

Who to marry

“Who to marry” is a very different external question. Once you have become motivated to marry, recognizing and being ok that the internal “you” will change because of being married, then the external question of who to marry is a simpler question. This is where traditional weighted cost-benefit criteria analysis may be applied. Criteria to consider include - Are they adaptable and ready to marry? Do they need to be in a certain geography? Do they wish to have children? Do they want to stay at home or work? Are they interesting conversationalists? Are they financially compatible? Or many others. In this case, since you are ready to marry, the criteria for who to marry are mostly focused on the available suitor population.

Notice that all these criteria have in common are that they are external to you. “Who to marry” is found in the Pareto framework as compliance with what is important to you today. The ”who to marry” question is found in the orange circle “compliance likelihood” part of the Pareto framework. Of course, the "who to marry" criteria will likely evolve as you learn. Thus, it is good to periodically update your criteria model. Also, notice the “whether” your suitor is ready to marry is in this “who to marry” compliance category of the Pareto framework. Presumably, your suitor is using a similar process. So their “who to marry” category likely evolves. This evolution occurs via the courtship process.

As a practical matter, “who to marry” does not always follow “whether to marry.” As an example, my wife and I met in college. I was an 18-year-old sophomore; she was a 17-year-old freshman. When we first met, without question, we were not ready to get married to anyone. But we both suspected that when we were ready to get married, we may be good for each other. So we dated, informally fine-tuned our “who to marry” criteria, and continued to grow up. Finally, about 7 years after we met and after she finished graduate school, we mutually decided we were both ready to marry. At that point, who to marry was the easy question to answer. We chose each other.

Are we ready? Overlaying value and compliance

There are likely many suitors that could be found in your good "who to marry" compliance category and there is likely little difference between “good” and “great” once you are ready. Readiness to marry is found in your value category. In the modern age, there are many dating platforms like Match, eharmony, SilverSingles, and others. Part of the process is that the participant needs to provide information and work at finding the best match. It is their willingness to apply the effort that is the "whether to marry" motivation signal. As the marriage motivation increases – as found in the value Pareto category - the likeliness that they will find a compliant “good” match expands – as found in the compliance Pareto category. Ironically, this occurs NOT because the platform’s matching algorithm improved, but because the participant is more motivated and accepting of possible suitors. Thus, the effort of the participant, via inputting their information, actively searching, updating, contacting, attending to the suitor, etc. is a self-selecting tell as related to the “whether to marry” category.

The previous section may feel weird, like the suggestion that love and matchmaking are little more than a probabilistic numbers game of optimizing value, subject to behavioral compliance for achieving that value potential. This game cascades through an internal and external-based matching process. A significant part of that process is a two-way internal paradox that relies on vague, self-referential data from our feelings. This may be true from a top-down view. Certainly, for those experiencing the bottoms-up process, it is full of uncertainty, hope, potential love, potential heartbreak, and desire to flourish. Riffing on Donald Rumsfeld - the more we attend to what we know, manage the known we do not know, and can deal with not knowing what we do not know, then the better we can use tools and make the most of the process to achieve our love potential.

The college decision similarity

As a former college recruiting partner at a large consulting firm, I consider the college decision as a similar two-step, value and compliance comparison process to marriage. First, the step one value question is - "are you ready for college?" For example, for high schoolers considering college, did they get the high school grades demonstrating their readiness? People sometimes misunderstand what grades signal. Grades do NOT imply whether someone is "smart." Grades signal whether a student has developed the STUDY SKILLS necessary to sustain 4 years of consistent, focused effort. Grades suggest whether a student can prioritize the hours necessary to study rather than going to a party or some social event. If the student did not demonstrate the study skills in high school, that student is less likely to manufacture them over the summer before their freshman year in college.

Then, comes the more challenging two-way internal question. Do they feel a desire to further their knowledge and position themselves for success with future employers? Can they see themselves flourishing in the workforce 5 years from now? Statistics show that students from first-generation college families are significantly less likely to be successful in college than those from legacy-generation families. I suspect this is because legacy-generation family culture helps the student resolve their self-referential challenge. The legacy-generation family helps their student understand what their "future you" looks like.

However, the step two question decision - which college to attend once college readiness is confirmed - is much simpler. Of the 4,000 or so colleges in the United States, almost all of them know how to put on a good college show. When I see college students drop out, it is almost always because they were not ready – related to the internal two-way question. The drop-out is NOT usually because there was something wrong with the college, as related to the external one-way question. Also, if the high school student is not ready for college, especially because of grades, I encourage them to attend community college. This is a low-cost option to determine college readiness. If they get good community college grades, they can always transfer to a four-year college. If they do not get good grades - at least they did not pay so much to find out they are still not ready.

Example summary

Finally, decision-making benefits from tools. The traditional, early-generation cost-benefit algorithmic analysis can be helpful for some decisions but is not as helpful for wild problems like marriage. However, if we pull those wild problem decisions apart between "whether" and "which," cost-benefit analysis is helpful for the “which.” Even in the case of self-referential decision problems, tools that help separate "good" judgment from bias are useful. More advanced, later-generation cost-benefit tools are called "choice architecture," which integrates behavioral capabilities to separate judgment from bias. The Pareto approach is useful as the stopping heuristic for self-referential decision problems. The following decision map captures many of the decision examples discussed earlier.

4. Conclusion

Over one hundred years ago, Vilfredo Pareto developed the 80/20 science to implement Voltaire's aphorism to discourage letting "Perfect be the enemy of good." In the decision sciences and choice architecture world, this helps us think about making decisions involving regular, life-improving trade-offs. While "running from the lion" was a helpful decision our ancestors made, today, we need to regularly make more complex trade-off decisions. A healthy debt repayment method, a healthy smoothie example, a medical challenge, and a marriage decision were provided to demonstrate the Pareto Principle in action. This trade-off framework is helpful for all modern-day decisions. Next, is an easy-to-use app and group decision choice architecture resources to help you make the best decisions in a complex world.

5. Resources

Definitive Choice: For individual or small organization groups - This smartphone app provides a convenient way to enter and weigh your preference criteria, then, enter your potential decision alternatives and their costs. Behind the scenes, it uses decision science to apply your tailored preferences and preference weights to score each of your alternatives. Ultimately, it renders a rank-ordered report to help you understand which alternatives will give you the biggest bang for your buck. Using a decision support app will 1) save you time, 2) optimize your economic value achieved, and 3) increase your decision-making confidence!

Definitive Pro: For corporate and larger organizations - This is an enterprise-level, cloud-based group decision-making platform. Confidence is certainly important in corporate or other professional environments. Most major decisions are done in teams. Group dynamics play a critical role in driving confidence-enabled outcomes for those making the decisions and those responsible for implementing the decisions. Definitive Pro provides a well-structured and configurable choice architecture. This includes integrating and weighing key criteria, overlaying judgment, integrating objective business case and risk information, then providing a means to prioritize and optimize decision recommendations. There are virtually an endless number of uses, just like there are almost an endless number of important decisions. The most popular use cases include M&A, Supplier Risk Management, Technology and strategy portfolio management, and Capital planning.

6. Notes

[i] Editors, Voltaire, Wikipedia, Accessed 6/4/2023

[ii] Economists refer to the value we receive from our "what is important to me or us" criteria as utility. "Utility" is the core driver of demand and is the aggregation of preferences we have for a good or service. Our economy operates via the interaction between supply and demand. As such, understanding utility is at the core of successfully navigating the modern economy. Understanding our utility is surprisingly complex and challenging.

Hulett, Assessing value like Warren Buffett: Price is what you pay, value is what you get, The Curiosity Vine, 2022

[iii] In the cited article, discussed are the challenges of and approaches to achieving long-term health and minimizing chronic disease. The cited article provides a Pareto Principle consistent example for implementing healthy behaviors as a means to achieve a long and healthy life.

Hulett, Getting the Most Out of America's Sickcare System, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[iv-a] Our hard-wired fight or flight decision-making processes have a subtle and significant impact to our day-to-day decision-making. Good follow-up questions to understand the importance and impact of our subconscious decision-making routines are:

How many generations came before me? and

What is the probability that I am here today as a product of all my ancestors?

Adam Frank is an astrophysics professor at the University of Rochester. Dr. Frank estimates there have been 400 human generations between now and the beginning of humanity. While your ancestral tree branched off from the first human generation, we all have about 400 generations. Now let's do some quick math. In the case of generational math, probabilistic combinations are serially dependent. This means that for you to be alive today, every preceding generation had to live long enough to have children. If there was one break in the chain, you would not exist! The formula for the dependent serial combination is:

The chance of you being alive today = P^N

where:

P is the average probability of all generations living long enough to have children and

N is the number of generations.

So, very conservatively, let us say there is a 90% chance since the beginning of time that each of your ancestors lived long enough to have the next child in your generational line. Since there are 400 generations, the probability you or any of us are here today is an astoundingly low probability approaching 0 (.9^400 equals a super small number with 19 zeros to the right of the decimal point!)

That means you are exceedingly rare. Your existence is a probabilistic rounding error. No wonder your genetic decision-making code has been hard-wired for fast fight-or-flight decisions. It was the precious few people that escaped from the lion to have children! The vast majority of "lion snack peeps" did not live long enough to pass on their slower decision-making DNA.

Frank, Who Were Your Millionth-Great-Grandparents? National Public Radio, 2017

Author's note: Intuitively, 400 generations seems low when compared to the estimated age of the homo sapien species. It is estimated homo sapiens have been a distinct species for about 300,000 years. However, even if the number of generations is higher, the point is still the same. Your existence today is an exceedingly low probability.

Hulett, Solving the Decision-making Crisis: Making the most of our free will, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

Hulett, Fight or Flight Decisions: The making of today’s decision challenges, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[iv-b] For typical decision-making cognitive biases and how they impact confidence, please see:

Hulett, Great decision-making and how confidence changes the game, The Curiosity Vine, 2022

[v] Hulett, Great decision-making and how confidence changes the game, The Curiosity Vine, 2022

[vi] Editors, Vilfredo Pareto, Wikipedia, Accessed 6/3/2023

[vii] Editors, Why Most New Year's Resolutions Fail, Lead Read Today, The Ohio State University Fisher School of Business, 2023

Behavioral Economists approach non-compliance by suggesting commitment devices. These are automations, such as auto transfer to an investment account from your regular paycheck, that enforce compliance. I am a big fan of commitment devices, especially for personal finance. Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler's groundbreaking research helped pave the way for the widespread use of commitment devices.

Thaler, Sunstein, Nudge, The Final Edition, 2021

[viii-a] In the graphic at the beginning of this article, the marginal benefit would be the first derivative of the blue value line. The marginal cost would be the first derivative of the orange compliance line. So, one only needs to eyeball the bad-good-great segments. In the bad segment, it is clear the slope of the value curve is much greater than the slope of the compliance cost curve. This means moving toward good is economically beneficial. Also, in the great segment, it is easy to see that the slope of the value curve is much lower than the slope of the compliance cost curve. This means stopping at good is economically beneficial.

[viii-b] To explore why our Bad, Good, and Great definitions are user-defined, please see:

Hulett, Becoming Behavioral Economics — How this growing social science is impacting the world, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[ix] Mullainathan, Shafir, Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, 2013

[x] Ramsey, The Total Money Makeover: A Proven Plan for Financial Fitness, 1994

[xi] Hulett, “Boil Your Own Frog” ... and other high-energy eating habits, The Curiosity Vine, 2021

[xii] Autor, Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation, JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVES, VOL. 29, NO. 3, 2015

[xiii-a] Roberts, Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us, 2022

[xiii-b] Admittedly, I am fortunate to have grown up where I had those resources to listen to and was wrapped in an environment encouraging good outcomes that included marriage. Not everyone is so lucky. One of the most powerful examples of tough decisions is one of abortion. No parent or single mom should ever have to face this decision, but many do.

Peer-reviewed and time-validated research from the University of Chicago and Yale University (See Levitt and Donohue) shows the relationship between abortion and crime. The data suggests a strong causal relationship - about 50% explanatory power, which is very strong in the social sciences. The summary finding is:

Cause: If the child-bearing decision is distanced from the expecting mother;

Effect: Then an increased likelihood of crime will occur.

While my family did not face such challenges, the Levitt and Donohue research shows the power of family environment and the impact of family in making life-changing decisions. Clearly, abortion and marriage are very different kinds of decisions. But they both have one thing in common -- the children of those family environments are greatly impacted by their environment. For an adulting child, this is a similar life-impacting decision specific to marriage or a life of crime.

Levitt, Donohue, The Impact Of Legalized Abortion On Crime, The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, 2001

Levitt, Donohue, The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime over the Last Two Decades, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019

[xiii-c] Grant, Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know, 2021

[xiii-d] To explore the subtle and important differences between bias and noise, plus their respective operating cousins, accuracy and precision, please see:

Hulett, Good decision-making and financial services: The surprising impact of bias and noise, The Curiosity Vine, 2022

[xiv] Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, 1976

Comments