Becoming Behavioral Economics: The Social Science Revolutionizing Decision-Making

- Jeff Hulett

- Nov 7, 2023

- 17 min read

Updated: Jan 16, 2025

This article offers a personal journey into Behavioral Economics, exploring its history, influential figures, practical applications, and the mathematical foundations that support sound decision-making for individuals and organizations. Behavioral Economics merges insights from economics, data science, finance, neurobiology, and psychology to help us better understand real human behavior and decision-making. For those considering entering this field, I aim to provide valuable resources and examples from various areas impacting Behavioral Economics. Because this field is still relatively young, each expert brings a unique perspective—much like the “blind men” in the parable, each perceiving only a part of the “elephant.” By synthesizing these diverse viewpoints, we can begin to see the full picture of how behavioral economics informs decision-making and shapes our understanding of human behavior.

My Elevator Pitch:

"I'm a decision confidence builder! I help people make the best decisions by applying a consistent, repeatable decision process. I help people create wealth and health in their lives.

If we have a bit more time…

"I help people use their individual and group judgment, curate their data, and build confidence to make decisions delivering the greatest value in life."

This pitch demonstrates how Behavioral Economics enhances decision-making by integrating individual and group judgment, data selection, and confidence-building within a proven decision framework.

About the author: Jeff Hulett leads Personal Finance Reimagined, a decision-making and financial education platform. He teaches personal finance at James Madison University and provides personal finance seminars. Check out his book -- Making Choices, Making Money: Your Guide to Making Confident Financial Decisions.

Jeff is a career banker, data scientist, behavioral economist, and choice architect. Jeff has held banking and consulting leadership roles at Wells Fargo, Citibank, KPMG, and IBM.

Becoming Behavioral Economics

My path into this field mirrors the discipline’s evolution—a progression shaped by merging established fields, shedding outdated assumptions, and integrating fresh insights over time.

I have academic degrees in mathematics, finance, and economics. Early in my undergraduate studies, I viewed finance as a reliable path toward a banking career. Plus, if banking did not work out, I would still gain practical skills, like balancing a checkbook. In the late 1980s, the world was at the very beginnings of transitioning from the industrial era to the information era. While I appreciated a new world was upon us, exactly how that world would emerge was mostly unknown. But I did suspect data was going to be at the center of the new era. Back then, the internet was limited to government and research institutions, used primarily for file transfers. I built my own computer with an Intel 8088 chip, one of the earliest processors, and taught myself DOS and machine language. Back then, computers barely had enough memory for a simple spreadsheet. By today’s standards, it was like using an abacus.

Exploring the machine opened my eyes to the “metaphor of mind” that computers emulate—an idea even more relevant today as artificial intelligence brings us closer to that metaphor. I saw data’s future importance clearly: it was only a matter of when, not if, data would become central.

This awareness drew me toward economics, which lies at the intersection of finance, data, and human behavior, reinforced by mathematical rigor. This set me on the path toward Behavioral Economics, although I wasn’t quite there yet.

Relatively early in my banking career, I had a "Red Pill" moment of epiphany. If you ever saw the movie "The Matrix" with Keanu Reeves, you will know what I am talking about. This is when my behavioral economics passion rocket launched.

Before the Red Pill: When I was in grad school, economics was taught in the Paul Samuelson-impacted neoclassical economics framework. Dr. Samuelson "mathematized" economics in the 1950s based on his book called The Foundations of Economic Analysis. The math was great, the economic way of thinking was elegant, but there was a problem lurking in the underlying assumptions. To make the math work, economists needed to assume there was a single, rational outcome to an economic problem. These highly influential economists were like a hammer looking for a nail, and theoretical math was their hammer. Their elegant frameworks showed how markets converge on a market price and quantity - a convergent equilibrium based upon supply and demand mechanisms. Equilibrium could only occur based on the assumption that market participants have perfect information. That is, old-school economics assumed there is a single "rational" point upon which all people converged. Anyone with real-world experience knows this "perfect information-informed rationality" behavioral assumption is quite unrealistic. I call this flawed, old-school definition of rationality - "robo-rationality." At the time, this was like an itch I could not scratch. I knew something was not right — I just could not put my finger on it.

My Red Pill moment came when I came across the emerging field of Behavioral Economics, led by figures like Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler. Behavioral Economics was beginning to answer questions I had just learned to ask. Kahneman and Tversky’s Nobel-winning work, Prospect Theory (1979), overlaid behavioral psychology on traditional economics, challenging the robo-rationality assumption. Kahneman’s background as a psychologist helped reframe economic theories to reflect human behavior better. The rapid advances in neurobiology also supported this shift, explaining why psychology influences economic behavior in ways that often defy logical consistency.

Key neurobiological building blocks include:

Neurons, synapses, glial cells, neurotransmitters, and our brain’s remarkable, active adaptability - called "neuroplasticity."

The sheer volume and vast interconnection of these elements give rise to an emergent quality in our behaviors that is often challenging to predict — both by others and ourselves. This emergent quality is at the core of consciousness.

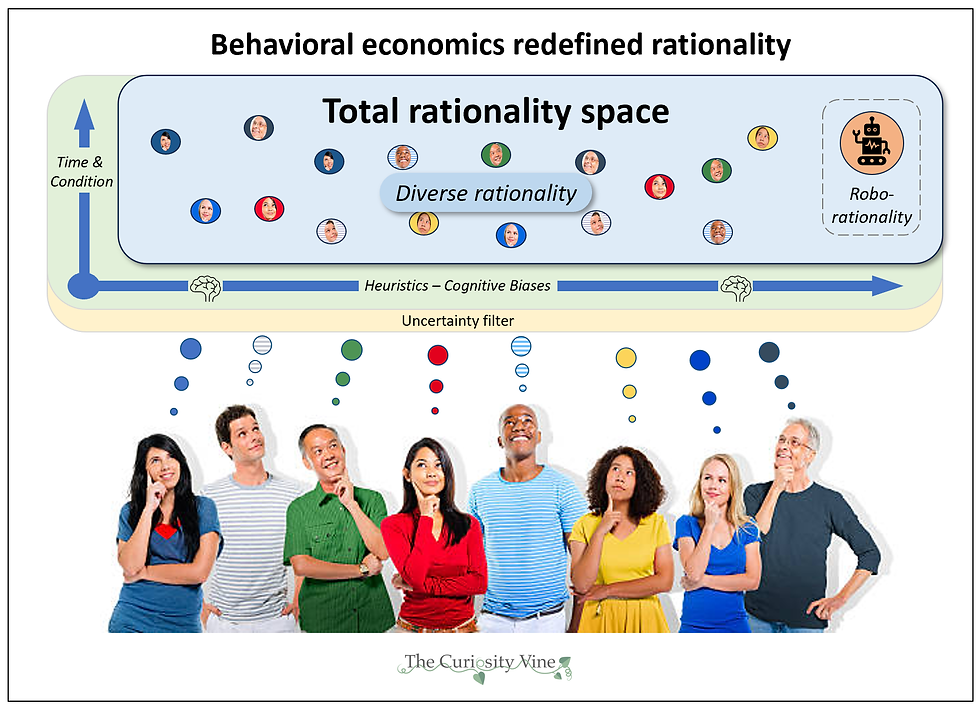

These components help explain why psychology-driven economic behavior can appear unexpected or inconsistent, paving the way for Behavioral Economics to redefine our concept of rationality. The red pill updated rationality definition is called “diverse rationality.”

Redefining Rationality

Behavioral Economics expands the concept of rationality to encompass the diversity in decision-making, acknowledging that heuristics such as situational framing, anchoring, and other contextual factors play a significant role in shaping individual choice. Rather than adhering to "robo-rationality," Behavioral Economics views people as adaptable, complex decision-makers. This adaptability, rooted in our brain’s fast-moving heuristics, is our species’ evolutionary superpower, enabling us to thrive in diverse and changing environments. However, it also brings cognitive biases—two sides of the same coin. Herbert Simon’s concept of "bounded rationality" aligns closely with "diverse rationality," illustrating how these mental frameworks complicate the notion of a universal rational model.

Diverse rationality captures a divergent spectrum of personal decision points across a broader space, reflecting unique conditions and changing contexts over time. Recent neurosemantics research by Shinkareva et al. supports this perspective by demonstrating that distributed patterns of brain activation can predict specific thoughts, revealing the brain’s individualized encoding of meaning. This research emphasizes that decision-making frameworks are deeply rooted in the neural structures and patterns unique to each individual, further underscoring the subjectivity of rationality [i-a]. What seems rational to one person may not to another, as these decisions are shaped by unique brain patterns, perceptions, and past experiences. Studies even indicate an individual’s diverse rationality can remain consistent over extended periods, framing rationality as fundamentally adaptive.

Thus, rationality is user-defined, reflecting our innate heterogeneity. [i-b][i-c]

Making decisions under uncertainty presents challenges for most people. Heuristics, along with companion cognitive biases, act as a filter influencing our perception and decision-making in uncertain circumstances. Influenced by evolutionary factors and rapid environmental changes, these biases are not always beneficial in modern decision-making contexts. Behavioral Economics, informed by insights from neuroscience such as neurosemantics, helps individuals and organizations adapt to the varied causes and effects of diverse rationality as it is. This is in contrast to the earlier approach defining how people ought to be rational

Embracing diverse rationality in economics unlocks a world of possibilities, some of which we will explore next. Although Paul Samuelson’s influential model of “robo-rationality” earned him a Nobel Prize, it presented a narrow view that Kahneman, Thaler, and Simon—each a Nobel laureate—would later challenge. Their work helped shift the field toward understanding the immense diversity in human decision-making. Even within academic circles, biases like inertia and groupthink can shape the acceptance of new ideas. [ii]

Interestingly, Nobel Laureate F.A. Hayek laid the early groundwork for this shift through his theory of mind, connecting neuroscience, behavioral psychology, and economics. He observed, “…to us is the starting point of all knowledge, namely the phenomenal order in which different stimuli appear in our mind.” By “phenomenal,” Hayek referred to conscious experience, while “stimuli” described the biological activity of neurons and synapses. Hayek’s view suggests that diverse rationality arises from the complex relationship between our inner experiences and the physical world. [i-b]

Falsification Leads the Way

One of the greatest strengths of Behavioral Economics is its commitment to testability and falsification. Unlike Paul Samuelson’s theoretical models, which promoted assumptions about how people “ought” to behave, Behavioral Economics takes a scientific approach to understanding how people actually behave. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), considered the gold standard for establishing causality, are central to this discipline. These trials not only validate new ideas but also challenge older assumptions, leading to refinements and entirely new theories.

This emphasis on falsification places Behavioral Economics in line with the traditional scientific method. By observing real behavior through RCTs and natural experiments, Behavioral Economists can discard ineffective ideas and replace them with evidence-based insights. For example, Richard Thaler’s groundbreaking “Save For Tomorrow” program redefined how organizations approach savings incentives by rigorously testing its effectiveness in the real world. This process of continually refining and replacing ideas ensures that Behavioral Economics remains dynamic and adaptable, evolving to meet the complexities of human decision-making. In my roles at Citibank, Capital One, and Wells Fargo, RCTs were a cornerstone for insights into credit access and loan repayment behaviors. Yet, while generating insights was crucial, building a culture to update and scale these findings across large organizations presented an additional challenge. Maintaining rapid updates and operational efficiency for large-scale implementation is a cultural tightrope.

The Importance of Scale Units in Behavioral Economics

Data-intensive industries, from banking with long loan performance periods to consumer products with shorter time horizons, are increasingly leveraging behavioral economics through “scale units.” These specialized teams adapt insights to foster a deeper understanding of customer behavior across varied performance cycles. Many banks and consumer-focused companies now operate scale units. My friend, behavioral economist John List, has led similar organizations at Lyft, Uber, and Walmart.

Scale units are particularly effective in tackling the challenges presented by Goodhart’s Law, which suggests that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” [i-d] Goodhart’s Law captures the inherent uncertainty, the adaptability of human nature, and the entropy in decision-making systems—qualities constantly seeking paths of least resistance, often undermining the intended effects of well-meaning policies. This aligns closely with the Lucas Critique, [i-d] introduced by Nobel laureate Robert Lucas, who argued that economic models often fail to account for how individuals adapt their behavior in response to policy changes. Both highlight the need for adaptive frameworks, such as scale units, to continuously test and refine measures as behaviors evolve, ensuring that targets remain effective in achieving their intended outcomes.

The toughest right choices often find the easiest escape routes.

When test measures are transformed into policies or “nudge” targets, people naturally adjust their behavior in unforeseen ways, diminishing the measure's effectiveness over time. This adaptation means that initial Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) results may not hold steady as people adjust to the incentives or constraints. [i-d] To maintain effectiveness, scale units must regularly re-test and adjust these interventions, ensuring that policies and nudges remain aligned with real-world behavior even as it evolves.

As an interesting aside, much has been written about the “replication crisis” in social science research and testing. [i-f] While cases of sloppy or fraudulent work may play a role, I suspect the replication crisis has more to do with Goodhart’s Law and the unreasonable expectation that social science results remain stable over time.

Scale units counteract Goodhart’s Law by continually testing and adjusting behavioral insights. For example, a scale unit could adapt savings programs to stay effective as consumer habits and conditions shift, preserving the impact and predictive power of key measures. Thaler’s original "opt-out" savings model effectively makes not saving the more challenging choice, nudging people toward desired behavior. As behavior adapts, scaling beyond default settings—such as increasing saving capacity through reduced expenses and higher income—demands ongoing testing. This continuous updating ensures interventions remain effective and impactful over time.

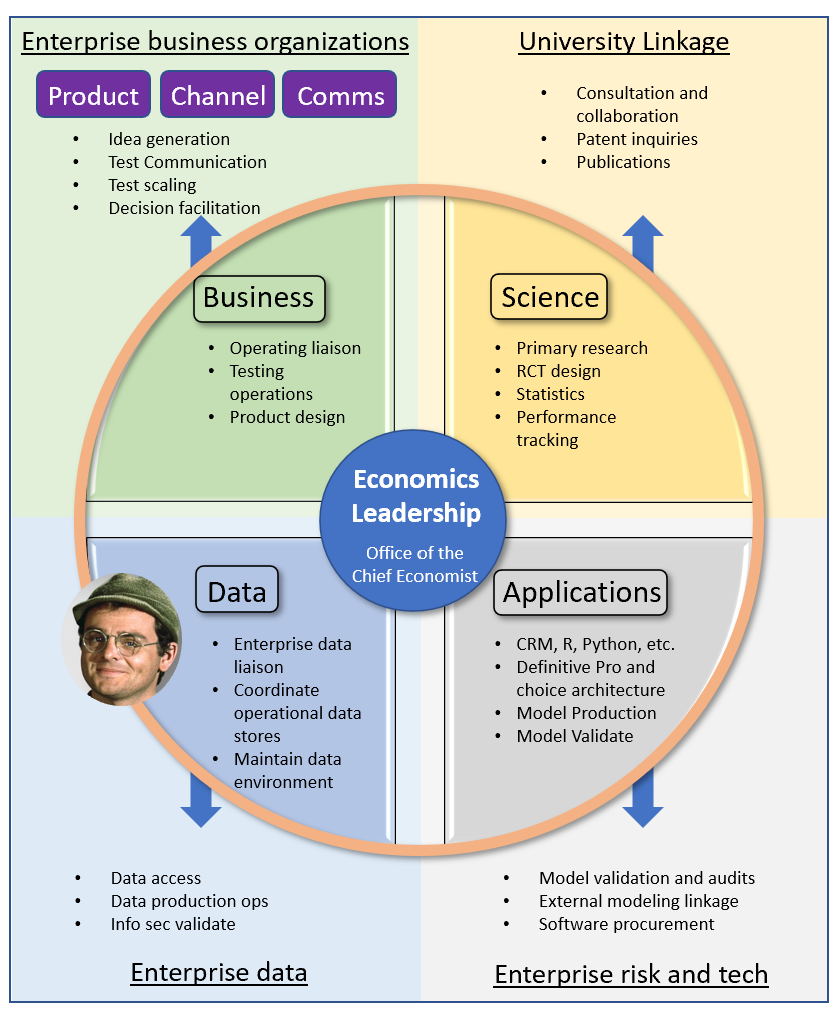

The Scale Unit

A scale unit is an analytics-focused team performing ongoing behavioral and automation-based testing, applying scientific principles to drive causality. Scale units act as a flywheel for long-term success by continuously refining insights and adapting policies to dynamic conditions. They are essential for sustaining Behavioral Economics insights over time, enabling organizations to adapt to Goodhart’s Law. By regularly uncovering changed measures and updating policies, scale units recalibrate nudges to maintain effectiveness.

Key benefits of a scale unit include:

Evaluating economic impact: Helping organizations understand the financial value of business activities designed to drive success.

Optimizing decisions: Recommending policies that balance risk with customer satisfaction and foster sustainable growth.

Enabling cultural adaptability: Supporting creativity and flexibility by continuously updating insights to respond to evolving consumer behavior.

Well-functioning scale units are cultural enablers for ongoing innovation, equipping enterprises to implement Behavioral Economics effectively and adaptively. For a deeper dive into scale units and their success factors, see The Business and Science of Scale - How Data, Decision Insight, and Economics Drives Success.

The scale unit flywheel

Framework to integrate economics into your organization

What’s Next: Complexity Economics and Diverse Rationality

Complexity Economics, led by thinkers like Doyne Farmer, elevates Behavioral Economics’ concept of “diverse rationality” to the macroeconomic scale. While Behavioral Economics has primarily influenced micro-level insights—focusing on individual decision-making and consumer behavior—Complexity Economics applies diverse rationality to larger economic systems, offering tools for government policymakers and macroeconomic applications. Unlike traditional econometric models, which often rely on “robo-rationality” assumptions, Complexity Economics recognizes from the outset that people and economic agents, such as organizations and governments, act within bounded rationality. This aligns with real-world diversity in decision-making, where choices are context-dependent and often limited by available information. Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) is an essential approach for realizing the value of Complexity Economics, allowing researchers to simulate interactions among diverse agents and anticipate emergent economic patterns on a macro scale.

Integrating Complexity Economics with Behavioral Economics provides a promising foundation for future policymaking. By accounting for the varied and bounded rationalities of individuals, organizations, and governments, Complexity Economics supports the design of adaptive, robust strategies mirroring the true complexities of economic systems. Macro-level scale units, equipped with Complexity Economics tools, offer a way to continually test and adjust policy measures in response to Goodhart's Law. These scale units enable policymakers to monitor shifts in behavior, adapt nudges, and refine metrics to maintain their predictive power and effectiveness, ultimately building resilience into policy frameworks. [iii]

Mathematics: The Foundation of Behavioral Economics

Mathematics is foundational to Behavioral Economics, supporting its scientific and technological applications. Calculus, including neural network backpropagation methods, is essential for modeling complex systems. While concepts from physics—like entropy and ergodicity—help explain uncertainty and variation. Financial insights, too, are grounded in math: convexity, for example, helps us navigate non-linear growth and understand the crucial difference between risk and ruin. Each of these mathematical principles links to how we understand and optimize decision-making.

Behavioral economists rely on RCTs (Randomized Controlled Trials) to test and validate hypotheses, often using statistical tools to compare control and test groups, gauge hypothesis strength, and scale findings. These principles also power Artificial Intelligence and machine learning, where statistics, Bayesian inference, and conditional probability are key to refining predictions and updating beliefs. Most choice architecture applies Bayesian inference to continually improve decision models. [iv]

Linear algebra, eigenvectors, and eigenvalues also play a practical role by enabling Behavioral Economists to specify individual utility functions—identifying what matters to each person in their purchasing choices. The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), a method developed by Thomas Saaty in the 1970s, is still widely used today to help define these utilities. We also use linear and non-linear programming to optimize decisions under various constraints.

While complexity mathematics is not a core part of Behavioral Economics, the growing synergy between Complexity Economics and Behavioral Economics indicates that concepts from dynamical systems and Chaos Theory may increasingly influence behavioral models. Techniques like the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) enable us to simulate individual or social group utility functions, making it possible to scale agent-based models incorporating diverse perspectives to inform policy. Complexity mathematics is particularly useful for simulating decisions under uncertainty and for understanding emerging risks.

Promoting Financial Literacy: A Personal Mission

Promoting financial literacy is a personal mission. We face significant challenges in financial education across the country. To this end, I started Personal Finance Reimagined - a decision-making and financial education platform. Our goal is to help people create and maintain a consistent, repeatable decision process to achieve a lifetime of wealth and health. Our platform includes books, research articles, videos, seminars, evidence-based insights, and other resources to reach our goals. We use our technology, what behavioral economists call “choice architecture,” as an essential enabler of our mission. I also teach personal finance at James Madison University and lead Definitive Social, a non-profit dedicated to providing choice architecture resources to those who need them most.

Choice Architecture in Action: The Role of Definitive

As an executive at Definitive, a Choice Architecture firm, I support decision-making tools implementing Behavioral Economics to help people make choices for best meeting their needs. Choice architecture counterbalances consumer platforms aiming to influence purchasing behavior in ways misaligned with a person’s true utility.

Definitive’s approach centers on three primary benefits, called DECISION A-C-T:

Acceleration: A nimble and engaging decision process that fosters swift, effective decisions.

Confidence: Building trust in the decision-making process so that people can move forward with assurance.

Transparency: Clear reporting and shareable insights that empower decision teams.

Conclusion

Behavioral Economics is a dynamic field, offering innovative ways to address complex challenges by applying insights from neurobiology, psychology, and economics. By recognizing that human decision-making is influenced by cognitive biases and situational factors, it redefines rationality to reflect diverse perspectives and contexts. This approach moves beyond traditional models by emphasizing the importance of choice architecture, enabling people to make decisions better aligned with their true needs. Tools developed in this field balance the influence of consumer platforms that often prioritize profit over individual utility. As Behavioral Economics evolves, it increasingly bridges disciplines, providing a deeper understanding of human behavior. Its applications are vast, ranging from public policy and finance to healthcare and consumer behavior. Through continuous adaptation, Behavioral Economics has the potential to shape how we approach decision-making in both individual and societal contexts, paving the way for more informed and beneficial choices.

Notes

[i-a] Shinkareva, S. V., Mason, R. A., Malave, V. L., Wang, W., Mitchell, T. M., & Just, M. A. (2008). Using fMRI brain activation to identify cognitive states associated with perception of tools and dwellings. PLoS One, 3(1), e1394. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001394

[i-b] F.A. Hayek suggests diverse rationality in his book "The Sensory Order." Hayek is one of the earliest to recognize the connection between neuroscience, behavioral psychology, and economics. As will be discussed later, Adam Smith certainly understood this connection, but he lived before neuroscience existed.

Much of Hayek's libertarian-focused choice model is built upon the observation that human decision-making and motivations are subject to complex and unpredictable interactions with their consciousness and unconsciousness.

Consciousness research is very active today. There are many high-impact theories. One I find very useful, especially because of the testing occurring to refine the theory comes from Stanislas Daehaene and his research team. Dehaene's theory of consciousness is known as the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory (GNWT). This theory suggests consciousness arises from the global broadcasting of information across a network of interconnected brain regions, allowing for widespread access to various cognitive systems like memory, language, and decision-making.

Dehaene, S., & Changeux, J. P. (2011). Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron, 70(2), 200–227. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.018

[i-c] "The persistence of diverse rationality" cases are where immediate modest payoffs crowd out needed investment to achieve much greater long-term benefits. Next are examples provided by Korteling, et al, 2023 -

"For example, it often seems to underestimate the long-term dangers of things like global warming and species extinction. This can make even major future threats seem insufficient motivation for determined action (Berger, 2009). In general, we see these types of typical, and often flawed, decision-making patterns in many different contexts of our society (Eigenauer, 2018). For instance, Flyvbjerg (2009) showed that 9 out of 10 transportation infrastructure projects end up in large cost overruns, which did not improve over time, even over a period of 70 years. Other examples of persisting problems that for a major part follow from poor decision-making are: improper and incorrect diagnoses as well as harmful patient decisions in medicine and health care (Croskerry, 2003; Groopman, 2007); overly optimistic growth assessments and ill-advised lending policies in global finance (Shiller, 2015); optimistic decision making in personal finance, like susceptibility to scams (Modic and Lea, 2013); against all knowledge continue a chosen course or investment with negative outcomes rather than alter it (Arkes and Blumer, 1985; Garland and Newport, 1991); perpetuating injustice through personal prejudice and unjust sentencing (Benforado, 2015)"

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

This paper introduces key concepts of heuristics, such as availability, representativeness, and anchoring, which are central to understanding cognitive biases in decision-making. It remains one of the most widely cited articles in the field of behavioral economics and psychology.

[i-d] Goodhart’s Law—“when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”—has been explored and tested in various ways across disciplines, though it is inherently challenging to “test” as a single hypothesis. Instead, researchers have examined its effects in specific contexts, particularly in economics, education, and management, where metrics are often tied to incentives or policy goals.

Goodhart, C. A. E. (1984). Problems of Monetary Management: The U.K. Experience. In Monetary Theory and Practice (pp. 91–121). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Here are some studies that examine the principles of Goodhart’s Law or similar concepts, often indirectly:

1. Strathern, M. (1997). “‘Improving Ratings’: Audit in the British University System.” European Review, 5(3), 305-321.

• Strathern’s work in educational settings highlights how performance measures, once tied to institutional funding or rankings, can prompt unintended adaptations that reduce the measure’s effectiveness—illustrating Goodhart’s Law in action.

2. Jensen, M. C. (2001). “Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and the Corporate Objective Function.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 14(3), 8-21.

• Jensen discusses how setting performance metrics (e.g., stock price) as primary targets can lead organizations to prioritize short-term gains over long-term stability, often undermining the quality of the original measure. This aligns with Goodhart’s Law by showing how metrics can lose validity when used as targets.

3. Espeland, W. N., & Sauder, M. (2007). “Rankings and Reactivity: How Public Measures Recreate Social Worlds.” American Journal of Sociology, 113(1), 1-40.

• This study investigates the effects of law school rankings, showing how schools adapt their practices to improve rankings, often at the expense of broader educational goals. The reactivity observed reflects Goodhart’s Law, as metrics shift focus from quality to rank-driven behaviors.

4. Frey, B. S., & Osterloh, M. (2012). “Stop Tying Pay to Performance.” Harvard Business Review, 90(11), 104-107.

• Frey and Osterloh critique performance-based pay by examining how individuals and organizations may manipulate measures, reducing their effectiveness and leading to unintended consequences. This work reflects Goodhart’s Law’s impact on the validity of performance metrics.

5. Manheim, D., & Garrabrant, S. (2018). “Categorizing Variants of Goodhart’s Law.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.04585.

• Manheim and Garrabrant categorize different variants of Goodhart’s Law, analyzing scenarios where the law is observed and suggesting how metrics can degrade once optimized for targets. Their work is more theoretical but explores potential solutions and considerations for designing better metrics.

These studies collectively show how Goodhart’s Law manifests when metrics are tied to targets, leading to “gaming” of the system, strategic adaptations, or unintended behaviors that undermine the original purpose of the measure.

The Lucas Critique:

Lucas, R. E. Jr. (1976). Econometric policy evaluation: A critique. In K. Brunner & A. H. Meltzer (Eds.), The Phillips Curve and Labor Markets (pp. 19–46). Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. New York: American Elsevier.

This work is foundational in macroeconomics and critiques the use of traditional econometric models for policy evaluation, emphasizing the importance of accounting for changes in individual behavior in response to policy shifts.

[i-e] Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., & Madrian, B. C. (2018). “Behavioral Household Finance.” In Handbook of Behavioral Economics: Applications and Foundations 1 (Vol. 1, pp. 177-276). Elsevier.

[i-f] Open Science Collaboration. (2015). “Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science.” Science, 349(6251), aac4716. DOI: 10.1126/science.aac4716

[ii] Even Kahneman, Thaler, and Hayek cannot claim to be the originator of behavioral economics. Much of the generalized behavioral economics framework was specified by Adam Smith in his book The Theory of Moral Sentiment, published in 1759. The interactions of a varying set of potential rationalities across people were theorized as the "invisible hand" and operationalized by Smith's framework: "The Four Sources of Moral Approval."

Kahneman, Thaler, Simon, and Hayek steered economics back to the more holistic Adam Smith road after Samuelson created a well-intended but less-than-accurate mathematical offramp. It should be noted that Nobel laureate economist F.A. Hayek laid some of the behavioral economics groundwork with his theory of mind, published in 1952.

Adam Smith defined the invisible hand as the mechanism by which all our preference bundles, via the market process, dynamically interact to settle on a single market price equilibrium. He also defined the "Impartial Spectator" as an imagined aggregation of all those that you respect and want to do well by. The impartial spectator is like your 'conscience person' by which you compare and evaluate all your actions. While Smith does not explicitly relate the impartial spectator to God or some deity, you may interpret the impartial spectator as such. Smith wisely leaves it up to the reader to define their own impartial spectator to help guide decisions under uncertainty.

Adam Smith, of course, did not have the benefit of modern neurobiology or behavioral psychology to inform his deductions. His deductive intuitions have stood the test of time.

Thus, while time has not validated Samuelson's theories on rationality, time has validated Smith's theories on moral sentiment, the impartial spectator, and the invisible hand. It is interesting, perhaps consistent with the Lindy Effect, that Smith's work was published almost 200 years before Samuelson's.

[iii] Farmer, J. D. (2024). Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World. Yale University Press. This book explores complexity theory’s principles, providing insights into how diverse rationality functions within complex economic systems and its implications for more effective policymaking.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99-118. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884852. This foundational work introduces bounded rationality, supporting the application of diverse rationalities across different economic agents.

[iv] Hulett, Changing our mind and using Bayesian Inference in our day-to-day life, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

Comments