Work Until You Die—And Love Every Minute

- Jeff Hulett

- Sep 21, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 22, 2025

Why Retirement Is the Worst Word in the English Language.

If there is one thing America has all wrong, it is our relationship with work. In the United States, the cultural norm is binary: you work for four or so decades, then you retire. Retirement is cast as the opposite of work—leisure, rest, withdrawal. Institutions from Social Security to Medicare reinforce this framing, treating life as a switch you eventually flip from work to non-work.

Yet this binary model hides deeper dysfunctions in how Western economies organize work. Claire Cain Miller’s influential New York Times piece “Greedy Work” highlights how many high-paying professions demand long, inflexible hours that crowd out family and other essential pursuits. Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin’s research shows how greedy work reflects employer incentives—rewarding availability while sidelining flexibility—and in the process eroding balance and well-being for workers across the board.

American employment law has quietly reinforced these dynamics. Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), most knowledge workers are classified as “exempt” employees, meaning they do not earn overtime pay beyond 40 hours. Every additional hour worked is effectively free to the company but carries a steep personal cost to the worker—draining time, family life, and health. These legal and structural incentives make greedy work the default for professional careers, pushing people deeper into the binary of decades of sacrifice followed by abrupt retirement.

About the author: Jeff Hulett leads Personal Finance Reimagined, a decision-making and financial education platform. He teaches personal finance at James Madison University and provides personal finance seminars. Check out his book -- Making Choices, Making Money: Your Guide to Making Confident Financial Decisions.

Jeff is a career banker, data scientist, behavioral economist, and choice architect. Jeff has held banking and consulting leadership roles at Wells Fargo, Citibank, KPMG, and IBM.

Defining Retirement: Beyond the Binary

Retirement does not have to mean withdrawal. At its best, it is a transition in how people define and receive value from their work. The traditional American model assumes retirement marks the end of employment and the beginning of leisure. But this view is too narrow.

In reality, people continue to create value throughout their lives, and value can be recognized in multiple ways:

Monetary pay. Some choose to remain engaged in work that pays directly for their expertise, with compensation that may even grow as wisdom and networks deepen.

Flexibility as currency. Others trade higher earnings for autonomy—working fewer hours, choosing projects, or enjoying location independence. Flexibility itself becomes a form of payment.

Hybrid rewards. Many find joy in arrangements that combine financial pay with lifestyle benefits—earning income while also gaining time, mobility, or creative freedom.

Purpose-driven contribution. Work that provides meaning and joy is its own reward, sustaining well-being in ways pure leisure rarely can.

The point is not whether retirement involves traditional employment or leisure, but how value is recognized—whether through money, flexibility, autonomy, or other rewards that matter to the individual.

In fact, I do not like the word retirement at all. In the American context, it reinforces a binary mindset of “work” versus “non-work.” What we need is a different vocabulary—one with an age-agnostic framing of work as a lifelong gift, continually redefined to provide benefits, purpose, and fulfillment at every stage of life.

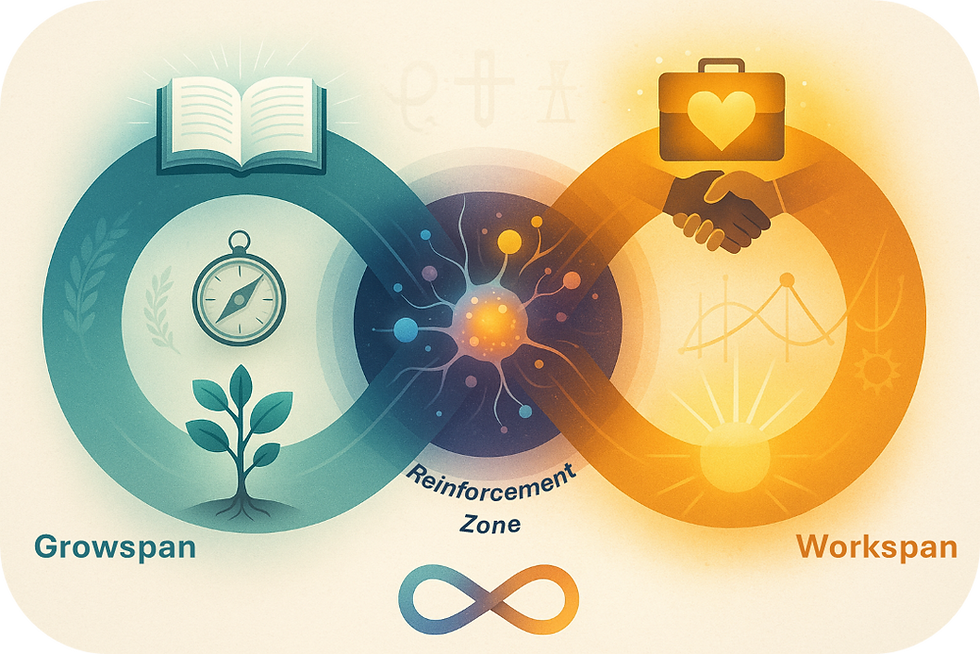

Instead, I think in terms of a growspan and a workspan. These are not separate stages but deeply integrated, developing side by side. The growspan emphasizes learning—education, exploration, and building the habits and skills that form the foundation for future growth. The workspan emphasizes applying those investments in purposeful activity—creating value, adapting with circumstance, and finding fulfillment. Much like Wright’s Law, where experience drives down costs and accelerates productivity, the growspan and workspan reinforce one another: learning fuels more effective work, and work experience in turn accelerates deeper learning. Together they magnify the impact of our contributions over a lifetime.

Defining Work: A Gift, Not a Burden

Work is not simply toil; it can be a gift. Religious and philosophical traditions frame work as something God-given—providing purpose, structure, and a way to serve others. As the Apostle Paul wrote, “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters” (Colossians 3:23). Philosophers have echoed this truth in secular terms: Aristotle argued that human flourishing (eudaimonia) comes through purposeful activity, not idleness. Both perspectives point to the same conclusion—work is not merely a means of survival but a pathway to meaning, fulfillment, and service.

Modern voices reinforce this view. MIT labor economist David Autor observes, “Work is really wrapped up with identity. Work is not just money for most people.” His research highlights how work provides not only income but also dignity, structure, and connection—benefits markets often overlook when reducing labor solely to wages.

Modern neuroscience supports this perspective as well. Work engages a cocktail of neurotransmitters that shape motivation, focus, and well-being. Dopamine drives the anticipation of achievement and reinforces progress. Acetylcholine sharpens attention and supports learning in complex tasks. Oxytocin strengthens bonds of trust and collaboration, reminding us that much of work’s value comes from relationships. Serotonin helps regulate mood and provides a sense of contentment when our efforts align with purpose. Together, these systems create the conditions for “flow states,” where time feels suspended and satisfaction is high. In contrast, passive leisure rarely activates this full network, which is why it often delivers less enduring fulfillment.

Economics adds another layer: through comparative advantage, individuals create value when they align unique skills with the needs of society. In this way, work is not only a means of earning income but also a mechanism for contribution and identity.

When viewed as a gift rather than a burden, work becomes something to be shaped and evolved, not something to escape.

A Lifelong Evolution of Work

One way I live this philosophy is through Personal Finance Reimagined (PFR), the decision-making and financial education platform I founded. PFR equips students, professionals, and entrepreneurs with structured tools—like textbooks, smartphone apps, workshops, and CFO services—that help them grow businesses and make confident financial and career choices. For younger workers, PFR also builds a roadmap for saving and investing early, so the power of compound interest creates greater flexibility to adapt their work as they age. The work spans many domains: teaching in high schools and colleges, coaching student-athletes, advising entrepreneurs, and supporting founders and contributors.

For me and my PFR teamates, this breadth creates a portfolio of work that is flexible, adaptive, and resilient. Like a diversified investment portfolio, a work portfolio spreads risk, encourages innovation, and allows value to grow in multiple directions. As client needs evolve, PFR evolves with them. This design avoids the rigid, binary structures that can stifle growth and prevents work from becoming disconnected from purpose.

PFR’s culture is built around this idea. Our teammates are encouraged to view their contribution to PFR as one part of their broader work portfolio. For example, a fractional CFO may choose to devote 15 hours per week to supporting a handful of startup clients through PFR. They can do this remotely and balance it with other professional or personal pursuits. By embracing flexibility and autonomy, PFR helps people design work arrangements that honor both purpose and life balance.

Building PFR has required enormous effort—standing up a business, leading projects, taking risks, and managing complexity. Yet it is work I love, because it connects deeply to my purpose: empowering people with decision-making frameworks that last a lifetime.

Over time, my own work will evolve. Today, it may be focused on entrepreneurship, advising, and teaching; later, it may be something else. What remains constant is that work provides love, purpose, and joy. This echoes psychological research: people are happiest when they experience purpose, autonomy, and positive feedback loops in what they do.

Practical tips for building your own portfolio of work:

Diversify roles: Combine activities that pay financially with those that pay in flexibility or meaning.

Invest in adaptability: Choose work that allows you to shift focus as your skills and interests change.

Balance the timeline: Keep near-term projects for energy while cultivating long-term efforts that build legacy.

Align with purpose: Regularly assess whether your work portfolio connects with what brings you joy and fulfillment.

The key is not avoiding work, but ensuring it evolves with changing gifts and circumstances.

Retirement Reimagined: Work Until You Die (With Joy)

If I am fortunate and my plans work out, I will work until I die. That does not mean holding the same job forever; it means allowing work to adapt as my needs, talents, and sources of joy shift over time.

This perspective reframes retirement not as the absence of work but as its transformation. It rejects the binary model and instead embraces life as a continuum of evolving contributions. Just prior to death, my hope is to look back on a purposeful life where work and love were inseparable, not a life divided into decades of labor followed by decades of withdrawal.

Conclusion: Choosing Purpose Over the Binary

America’s binary model of work and retirement is limiting. It assumes work is inherently burdensome and retirement is the only path to freedom. But other cultures, faith traditions, and modern science show us that both work and retirement can be redefined.

Work is not merely what we must endure before reaching leisure. It is a gift providing purpose, focus, and connection. Retirement should not be an abrupt end, but a chance to evolve into new forms of contribution.

By rejecting the binary and embracing work as a lifelong source of joy, we can build lives that are both more purposeful and more fulfilling. The choice is not between work and retirement—it is to design a life where work and purpose walk hand in hand until the very end.

Resources for the Curious

Miller, Claire Cain. “Greedy Work.” The New York Times, April 26, 2019. – Explores how long, inflexible hours in high-paying jobs fuel inequality and limit family balance.

Goldin, Claudia. Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity. Princeton University Press, 2021. – Nobel Laureate Goldin’s research shows how work structures create persistent gender inequality.

Hulett, Jeff. “The Greedy Work Syndrome: Helping the Professional Services Industry Solve Investment Challenges.” The Curiosity Vine, September 13, 2021. Updated November 18, 2023. – Explores how U.S. labor law, professional services culture, and “exempt vs. non-exempt” employee status reinforce greedy work, and provides solutions for firms and policymakers.

Hulett, Jeff. “How Medical System Incentives Foster an Impaired, Health-Diminished Doctoring Environment.” The Curiosity Vine, June 9, 2023. Updated March 24. – Examines how the medical system’s structure encourages greedy work, sleep deprivation, and health risks for providers, with implications for professional services more broadly.

The Holy Bible. Colossians 3:23. – A foundational Christian teaching on the spiritual purpose of work.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Terence Irwin. Hackett Publishing, 1999. – Classical philosophy framing purposeful activity (eudaimonia) as the core of human flourishing.

Autor, David. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 109, 2019, pp. 1–32. – MIT labor economist Autor explains how work shapes identity, dignity, and opportunity in a changing economy.

Ulrich-Lai, Yvonne M., and James P. Herman. “Neural Regulation of Endocrine and Autonomic Stress Responses.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 10, no. 6, 2009, pp. 397–409. – Details how neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine interact in stress and reward, relevant to why purposeful work can regulate mood and build resilience.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row, 1990. – The classic work on how meaningful tasks create deep satisfaction through “flow states.”

Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Liberty Fund, 1981 [1776]. – The original articulation of comparative advantage and how individuals create value in society.

Comments